$CPRI / $TPR: Closing Arguments

Preliminary Injunction ruling in New York is right around the corner

Last Monday marked the closing arguments in the Section 13(b) preliminary injunction hearing for the Tapestry / Capri merger, held in S.D.N.Y. Court, so it’s time for a post-trial update! The trial, presided over by Judge Jennifer Rochon (a Biden appointee), included testimony from top executives at the Defendant brands, as well as from major retail leaders such as Jeff Gennette (Defendants’ expert witness and former CEO and Chairman of Macy’s Inc.) and Phillip Hamilton (Lululemon VP of Global Merchandising).

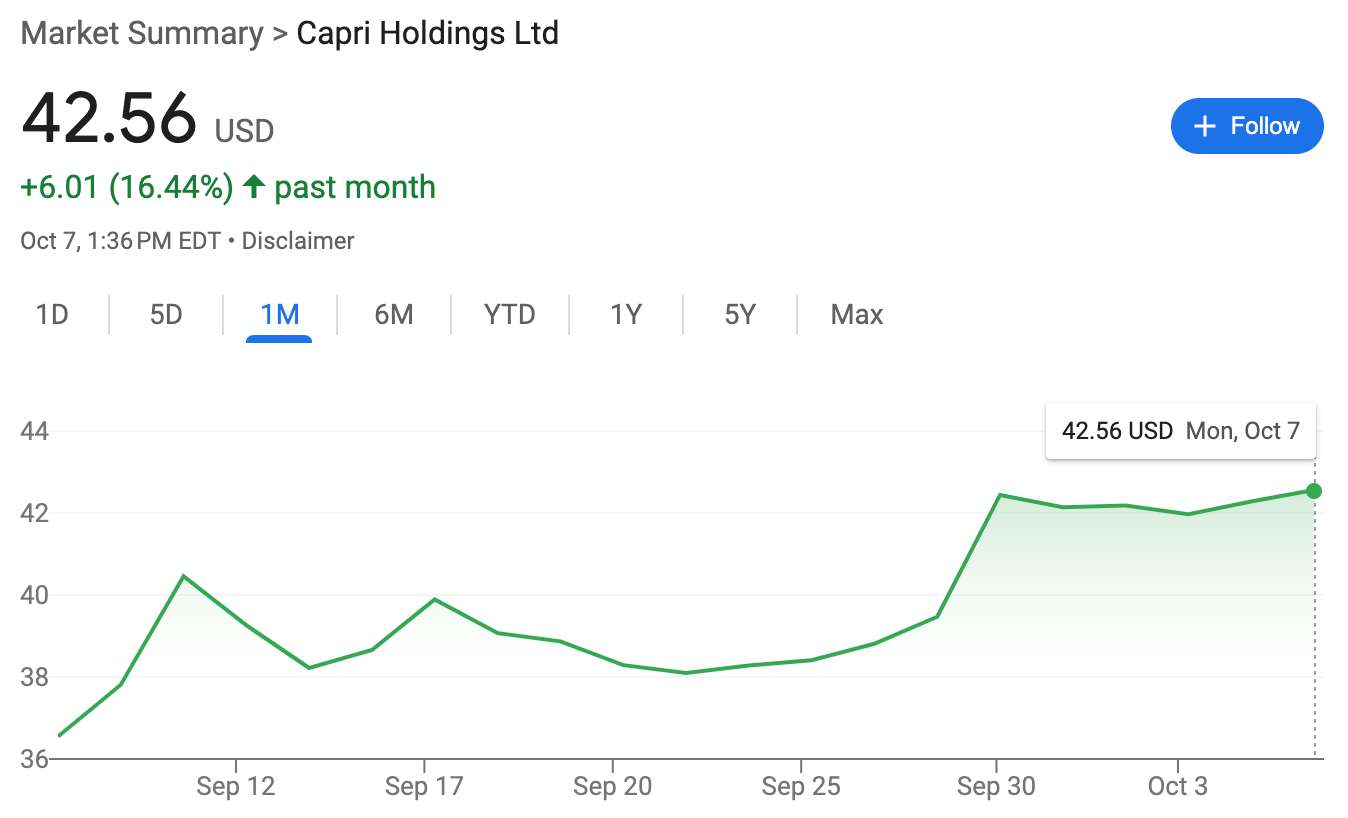

For those following along, the trial seems to have gone pretty well for the Defendants, and the stock price has appreciated materially over the course of the parties’ respective cases.

But are those gains justified?

By the accounts of those in the courtroom (I was unfortunately not in attendance), the FTC’s case was a meandering and sometimes confusing exercise in drawing physical parallels between products made by the merging brands. Every update I received was about the Defendants “scoring points” while the FTC seemed to flounder.

That may sound like a bit of my bias talking though. Throughout this FTC challenge, the Libertarian part of me has wanted to just say “who the heck cares if these companies merge??” and call it a day. Challenging a merger of purely discretionary products is sort of inherently dumb, especially when there’s almost no real barrier to entry for new competitors. And as the Defendants point out in their Proposed Findings of Fact (“PFOF”), with a purely discretionary purchase, the product doesn’t just compete with other products of the same type; the actual competition is between “a handbag [and] a piece of ready to wear . . . [or between] a piece of ready to wear [and] go[ing] out to dinner[.]”

It has always been a silly FTC challenge, made sillier by the fact that Lina Khan somehow convinced the two Republican commissioners to get behind challenging the deal. Nobody else seems to be bothered by the union, including China’s antitrust regulator. Hell, the FTC couldn’t even unearth a single industry player or consumer group that had concerns over the deal—a fact that really should carry a tremendous amount of weight, and which the Defendants won’t let the Court forget:

from Defendants’ PFOF

But the point of Valorem is not to act as a platform for my own political opinions. We’re trying to predict outcomes here. So it’s worth asking how there is so much water between American antitrust regulators and consumers, foreign antitrust regulators, and retailers alike. It’s also worth asking how there is still so much water between the ~$42 stock price today and the $57 deal price.

The answer—at least for the first question—is that the FTC has a new-ish legal theory on the line which it won’t let go. We talked previously (and above) about Tapestry and Capri’s investor disclosures and how “accessible luxury” is painted all over the SEC filings (let’s call it the “SEC Definition”). Despite the brands’ attempts to re-characterize the category as “expressive luxury” in response to the FTC suit, the “accessible luxury” or “affordable luxury” moniker has been used extensively by both companies. So a big question here is: just how far does a company’s own characterization of its market for investor purposes go in an antitrust suit, particularly when that definition is used by both merging parties who are undeniably each other’s main competitor.

There’s no doubt the SEC Definition paints Defendants into a bit of a tough corner. On top of that, the legal standard applied in these preliminary injunction hearings historically hasn’t been particularly helpful for Defendants. While it’s true the FTC must demonstrate a likelihood of success on the merits in the case, the Section 13(b) preliminary injunction standard was consistently weakened in the last few decades. Typically, the FTC doesn’t need to “win it all” here and prove it absolutely will succeed. Rather, prior courts have ruled that the FTC just needs to show that the merger warrants a closer look justifying a maintenance of the status quo. This specific legal standard that has been nestled under the broader likelihood of success standard, as the FTC notes out in its Proposed Conclusions of Law (“PCOL”), is whether or not there are sufficient serious questions on the merits to justify the injunction.

But that standard is now the subject of some debate, and may no longer be accurate. In the recent Supreme Court decision in Starbucks v. McKinney, the Court struck down the lower “substantial question” standard for government agencies seeking a preliminary injunction where Congress has not expressly permitted such lower standard. As Tapestry and Capri describe in their PCOL:

the Court held that, absent a contrary “clear command from Congress,” a federal government agency must make a “clear showing” of a likelihood of success on the merits to obtain a preliminary injunction. 144 S. Ct. 1570, 1575-76 (2024) (“likelihood of success” standard means what it says and requires more than just showing that the agency’s case poses a “substantial and not frivolous” question).

Following the Starbucks ruling, we got a district court ruling out of S.D.N.Y. in August of this year in the fuboTV Inc. v. Walt DisneyCo. case applying this new standard. The fuboTV Court, applying the Starbucks formulation of the preliminary injunction standard (i.e., a typical 4-part preliminary injunction standard requiring a legitimate finding of likelihood of success on the merits), found that Section 16 of the Clayton Act had no clear intent from Congress to depart from the common law standard, meaning the “substantial question” threshold was no longer the standard for Section 16 causes of action.

So will that ring true here as well? Is the FTC entitled to the lower “substantial question” standard under the FTC Act?

Similar to Section 16, Section 13(b) of the FTC Act does not appear to have any such broad mandate to issue an injunction on a lower “substantial question” standard. Indeed, it specifically enumerates the likelihood of success requirement:

from Section 13(b) FTC Act, 15 U.S.C. § 53(b)

That’s the good news. As far as I can tell, there’s nothing in the legislative history that would indicate Congress intended the FTC to have a lower burden for Section 13(b) preliminary injunctions.

The bad news is that, for every defendant ever, a grant of a preliminary injunction in a Section 13(b) trial acts to place a thumb on the scale in the subsequent administrative hearing, stacking the deck further in the FTC’s favor. As a matter of practice, almost all parties affected by a Section 13(b) injunction end up abandoning the merger, even before a Part 3 hearing in front of the FTC. And though that seems a bit unfair, there’s a practical rationale for the lowered hurdle in the district court injunction hearing: unscrambling the egg once the Defendants merge is much harder than simply delaying the merger until the FTC Administrative Law Judge (“ALJ”) can hear the case—even if the Defendants intend to maintain brand separation as they have asserted in Court.

Because it’s harder to unscramble the egg of two merged companies, the “safest” career move for Judge Rochon here is to issue the injunction, even if the injunction tilts the scales in the FTC’s favor. Given Judge Rochon has only been on the bench since June of 2022, that may be at the forefront of her mind—she’s fairly young and a future appellate appointment isn’t out of the question, so effectively punting here could serve to protect her judicial record. And given the Defendants’ own conduct with respect to “market” communications in the SEC Definition(s), and the fact the two companies are very obviously the biggest competitive threat to one another, that’s probably facially enough to give Judge Rochon grounds to enjoin the merger for now.

Still, an opinion enjoining the merger would have to reconcile some fairly serious flaws in the FTC’s arguments. There were quite a few points over the course of the trial that made me question the validity of the FTC’s arguments, but we’re going to focus on three in particular that might actually be fatal to the FTC’s case.