Grocery Games

Kroger / Albertsons + a Few Updates

Lately, everyone is complaining about their grocery bills. And while food inflation has come down, plenty of news outlets still seem confused by the concept that lower inflation does not mean prices come down.

With grocery prices remaining at these lofty levels, it’s no surprise that Biden has made food inflation—including “shrinkflation”—the subject of his State of the Union address and a target of his 2024 campaign. It’s also no surprise that Biden’s FTC, led by Libertarian-fan-favorite Lina Khan, has taken aim at the proposed Kroger / Albertsons merger.

Under Biden’s FTC and DOJ, as we learned with JetBlue / Spirit, big is bad. Mergers that are optically bad will get challenged, regardless of the competitive realities on the ground. Blocking big mergers is a win for the little guy, or at least that’s the campaign message Biden is telling.

But is the Kroger / Albertsons deal doomed like JetBlue / Spirit? It’s probably too early to tell. There are reasons to be more optimistic, though very cautiously so.

THE MERGER

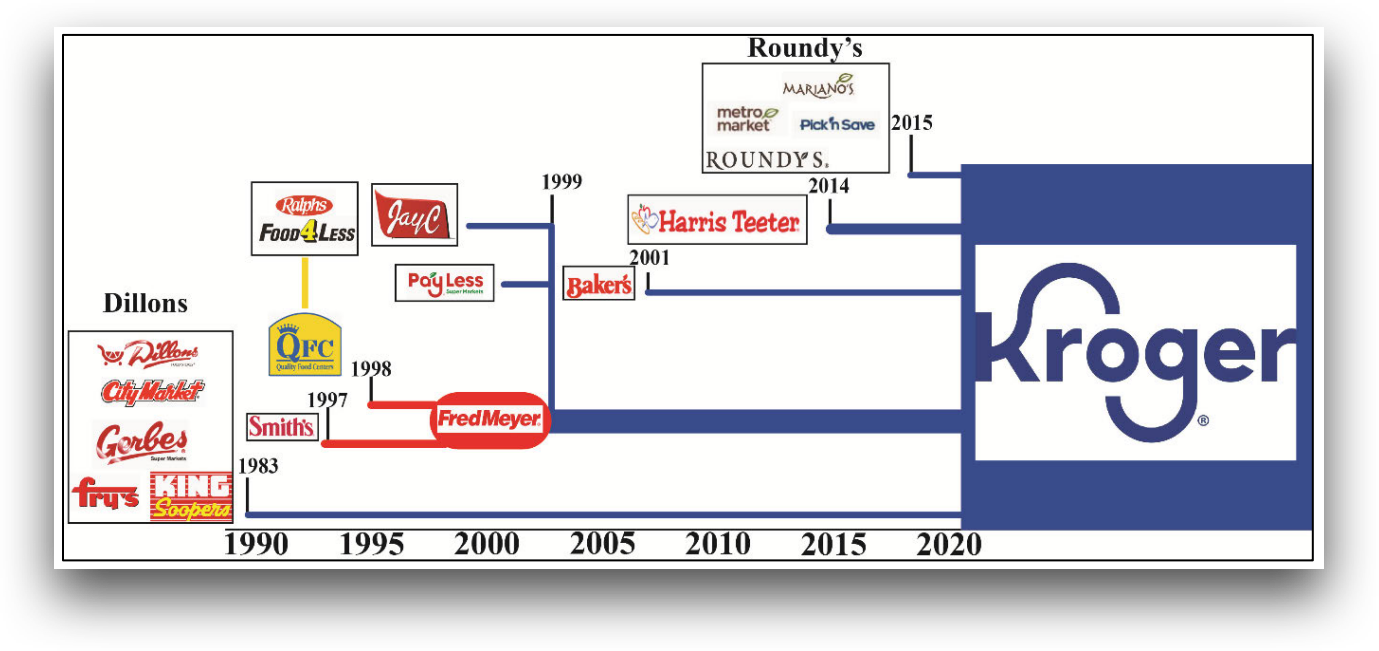

Grocery stores have been merging since the dawn of time. Or at least since the dawn of my time in the late 80s and early 90s. It’s a strategy that makes plenty of sense. Larger grocery retailers means economies can be found in larger orders from suppliers, cross-docking, inventory replenishment and storage, and direct-to-store delivery.

Despite the history of consolidation, the past mergers drew relatively little scrutiny, as mergers increased national concentrations but did not increase local concentrations where the pricing power would be felt. In other words, retailers were gaining economies of scale across the broader U.S., but these economies were actually getting passed on to consumers as the larger chains still had to compete with local grocers.

Even where deals were challenged, divestitures were able to cure regulators’ concerns. In 2001 during the pending Albertsons / American merger, Albertsons agreed to divest 104 Albertsons stores and 40 American stores across California, Nevada, and New Mexico, where combined market concentrations would be felt locally, to assuage the FTC’s concerns over the parties’ proposed merger. Some mergers required no divestitures at all. For example, Kroger’s 1998 acquisition of Fred Meyer and Yucaipa resulted in few divestitures due to a lack of material overlap in local markets.

Consequently, the national market concentrations of traditional grocers has continued to grow, as evidenced by the FTC’s complaint:

from FTC Complaint

from FTC Complaint

Admittedly, the graphics don’t look great for the merger. It doesn’t look that different from the graphics we saw in the JetBlue / Spirit merger. Some might say it looks even worse, with two dominant players instead of five.

But what has really been going on here? Have grocers really been snowballing into mega-corporations hell-bent on destroying your wallet and your hopes of a summer trip to Cancún? Are grocers’ margins increasing to untenable levels, aided by the last three decades of consolidation?

Not quite.

Consolidation has been the natural progression of the grocery industry, allowing larger players to merge operations, cut expenses, reduce costs and negotiate lower prices with suppliers, as mentioned. These economies of scale are true of almost any larger merger, but there’s the added issue of geographic food supply. Having a network of connected grocers with centralized distribution allows means you don’t need to set up shop right next to a farm to get the benefits of favorable supplier pricing, and consumers can get access to a broader selection of product offerings.

Consolidation doesn’t just make sense though; it’s become necessary, accelerated by the fact that larger retailers like Costco, Walmart, and Target are competing for grocery customers. These club and large-scale retailers, motivated by periodic declines in discretionary shopping, have been searching for ways to get customers in the door. Groceries, even with their relatively low margins, offer just that. For companies like Target and Walmart, it’s not really about making money on the groceries. It’s about getting you to buy a few t-shirts, some headphones, and a new tv because you already happened to be in the store during your weekly grocery trip.

In light of these emerging competitive struggles, Kroger announced a roughly $24.6B mixed cash and stock deal to acquire Albertsons in October of 2022, valuing Albertsons shares at $34.10/share.

The anomalous-looking drop post-announcement was attributable to the record date being Oct. 14, 2022 for a cash dividend component in the amount of $6.85 out of the $34.10 total deal consideration. So we’re looking at $27.25 remaining consideration for the deal.

THE CHALLENGE

As with JetBlue / Spirit, the challenge once again falls under Section 7 of the Clayton Act. This time, we’re dealing with the FTC, not the DOJ, but the jurisdiction over the transaction is fundamentally the same. Eight states (Arizona, California, Illinois, Maryland, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, and Wyoming) and the District of Columbia have joined the suit.

The primary challenge to the merger is that the increased concentration of the two grocers would lead to a substantial lessening of competition, resulting in higher prices for the end consumer. On its face, it seems reasonable enough. If there’s only one grocer in town, they can charge whatever they want. The combined entity would be the largest traditional grocer by miles, with a total of over 5,000 stores, 4,000 pharmacies, and 700,000 employees:

from D. Oregon COMPLAINT FOR T.R.O. AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF (Case No. 3:24-cv-00347)

It’s a merger that will impact the majority of the U.S., but the effects are alleged at the local level. That makes sense. In the best of times people aren’t likely to travel to the next town over for groceries. With gasoline prices where they are, that likelihood is near-zero.

But the FTC doesn’t just challenge the proposed combination’s monopoly power (i.e., one seller) of food pricing—there’s another aspect of the FTC’s challenge that is novel here, and therefore hard to handicap perfectly. It also alleges the proposed merger violates Section 7 of the Clayton act through the creation of a monopsony power (i.e., one buyer) with respect to union labor. The added harm, the FTC alleges, is that the combined entity would be the only “buyer” of union grocery labor across certain cities in California, Colorado, Oregon, and Washington.

Let’s break down these arguments a bit . . .

ARGUMENT: MONOPOLY GROCERY PRICING POWER

You may remember from our JetBlue/Spirit discussions that under the Baker Hughes antitrust analysis we need to first define a relevant market and then determine—in a series of burden shifting steps—whether or not the proposed transaction will substantially lessen competition in that market. The word “substantial” was conspicuously absent in some notable areas across the opinion Judge Young delivered in the JetBlue case, but the Clayton Act statute and bulk of the precedential case law is clear: incidental effects to competition, including temporary dislocations caused by the transaction itself, are not the types of effects the Court is concerned about.

The FTC proposes a seemingly straightforward definition for the relevant market:

from D. Oregon COMPLAINT FOR T.R.O. AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF (Case No. 3:24-cv-00347)

Specifically, the FTC elaborates, the store has to be a “one-stop shopping” experience. I think “one-stop” is a fair boundary to draw, but as we’ll see in a second the FTC overreaches a bit in its application of that term. And remember, the more narrow the relevant market, the more likely the FTC is to get a win, as it’s far easier to show outsized effects on small markets.

So assuming the FTC gets their definition, what exactly do they believe this definition excludes? Well . . . pretty much everything that isn’t Albertsons, Kroger, or your local family-owned grocery store that is either closed, in the process of closing, or closing soon.

More specifically, the FTC wants to exclude:

Club stores (e.g., Costco, Sam’s Club)

Limited assortment stores (e.g., Aldi, Lidl)

Premium natural and organic stores (“PNOS”) (e.g., Whole Foods, Sprouts Farmers Market)

Dollar stores (e.g., Dollar General)

E-commerce retailers (e.g., Amazon.com)

Grocery delivery services (e.g., Instacart, DoorDash)

It’s probably not necessary to talk about each of these in turn. E-commerce and dollar stores as easily distinguishable with respect to product offerings, geographic concentrations, embedded costs, etc. And I don’t think anyone is arguing that DoorDash should be a comp for Albertsons. There’s a non-trivial argument that delivery services expand the geographic scope of the relevant market, meaning that perhaps we should look at the greater Los Angeles region instead of, say Alhambra. But the reality is that these delivery cost get baked into the price the consumer pays, and delivery costs are not subsidized across the network (i.e., you don’t get a relative discount on delivery simply because you live in an area where the only producer is 50 miles away). You pay for that delivery. In sum, I think delivery service-related arguments are a long shot for Kroger.

The real debate will come down to whether or not to include club stores, specialty stores and PNOS stores. For reasons we’ll get into, I think the FTC is likely to succeed on excluding club and specialty stores, and lose on PNOS stores. Put another way, the relevant market is likely to include PNOS stores. That may not be enough to save this merger though.

Why do I think the relevant market will include specialty stores, but not limited assortment or club stores? Let’s start with PNOS stores.

PNOS stores, unlike the specialty stores, offer the “one-stop” experience that the FTC is ostensibly most concerned about—the kind of shopping experience that a typical family is doing once per week. Yes, Whole Foods and Sprouts are much more expensive than both Albertsons and Kroger, but nearly all categories of SKUs (e.g., canned goods, raw poultry, etc.) are accounted for. The mere fact that Whole Foods only offers “Whole Foods 365” paper towels and not Bounty, Brawny, or some other brand of paper towels is irrelevant to the average shopper, provided they’ve already accepted the higher pricing associated with shopping at Whole Foods.

And customers at PNOS stores are paying for quality. They’re paying to know that any product they buy will not contain certain preservatives or added chemicals that they believe makes products unsafe. That doesn’t change the fact that they must still compete for the weekly grocery shopper. If Whole Foods increased prices 100% across the board, most shoppers would consider Albertsons and Kroger as alternatives. There might be some shoppers who would continue to pay, but Kroger suddenly looks a lot more appealing. Similarly, if Kroger hiked prices post-merger by 100%, most customers would probably choose to purchase their groceries from Whole Foods. Even if the prices were the same as Whole Foods, customers would probably end up skewing towards Whole Foods because of the added natural/organic premium. In other words, there may exist some PNOS spread over traditional groceries.

I think of it like a credit spread. If you can buy a 10 year BBB corporate bond for 250 bps over the 10 year treasury, and suddenly Apple offers a 10 year bond for 350 bps over the 10 year treasury, the BBB bond price has to come down. They may be different classes, but they are, to some extent, fungible in that their pricing is always relative. Whole Foods may not be a direct competitor of Kroger and Albertsons, but the pricing must be taken into account on both sides. And you can certainly make the argument that post-Judge Young’s JetBlue decision the Court will only look to nearly-identical business models. But under the FTC’s own definition of the “one-stop shopping” experience, these PNOS stores should likely be included in the relevant market.

It’s also worth looking at where these stores actually compete with Kroger and Albertsons.

Here we see the distribution of Albertsons stores across the U.S.:

from Scrapehero

And here we see the distribution of Kroger stores across the U.S.

:

from Scraphere

We can see that Albertsons dominates the west coast and northeast, while Kroger dominates the midwest and southeast. The only real overlap is in select parts of the northwest, Southern California, and southwest (and a couple other pinpoint areas like Chicago, Phoenix, and Dallas).

What about the premium grocers then?

It seems unlikely that the availability of premium grocers is ubiquitous enough to make a difference here. For example, there are currently 516 Whole Foods stores in the U.S. across 45 states and 373 cities:

from Scraphero

There are currently 410 Sprouts grocery stores in the U.S. across 23 states and 295 cities:

from Scrapehero

These stores are—unsurprisingly—located in more affluent and urban parts of the country. Their presence is rare in the midwest, south, and even parts of the northwest where the overlap in Kroger and Albertsons stores is felt most.

So what about club stores then? Why should they, or should they not, be included in the relevant market definition?

Despite the FTC’s argument that club stores are entirely unique, and perhaps despite some hot docs that will likely show Albertsons and Kroger use each other as pricing anchors (we don’t know this, we’re just reading into the redacted docs), the fact of the matter is that traditional grocers are increasingly looking towards club stores like Costco and large retailers like Walmart and Target. The National Bureau of Economic Research highlighted this changing landscape back in 2011, finding that traditional grocers reduce prices by 1-1.2% when mass-retailers like Walmart enter a city. Costco has an even greater effect, forcing traditional grocers to reduce prices by about 1.4% in the short term and a whopping 2.7% on a longer time horizon.

Still, a couple things give me pause.

The first major problem is the hot docs, along with the judge’s inexperience not just with antitrust cases, but in federal cases as a whole. If Kroger has admitted that there are substantial antitrust concerns that cannot be mitigated, and that Albertsons is the best price comp, that’s going to be hard to overcome in front of a relatively novice federal judge. As I said above, we don’t know that’s what the hot docs say, but judging by context in the complaint, it seems like that is likely to be the case:

from FTC Complaint

from FTC Complaint

from FTC Complaint

Of course, Kroger execs will take the stand and say that the merger was concerning without divestitures or something to that effect, but we did see Judge Young latch onto certain hot docs in JetBlue / Spirit that I thought he would grapple more intensely with.

The second major problem is that it’s too easy to thematically distinguish the club store and traditional grocer business models. In my mind, it’s about (1) access, (2) demographics, and (3) experience.

Access: Costco and Sam’s Club might help lower prices for traditional grocer consumers, but there is a large swath of consumers who don’t have direct access to the beneficial pricing of the club stores. This may be due to an inability to front the membership costs and bulk purchasing, or it may be due to geographic constraints of actually getting to club stores, which require significantly greater footprints and are therefore typically located outside city centers.

Demographics: Costco shoppers might be Albertsons shoppers, but Albertsons shoppers are not necessarily Costco shoppers. Costco shoppers are historically older, college-educated, and making 6-figures. That consumer age profile has changed a bit in recent years, but the income levels haven’t. Costco customers are wealthy, and that’s a tough comp for Kroger when the FTC gets to tell a story about a small-town, price-sensitive family who can’t afford to buy a year’s supply of toothpaste in one go.

Experience: Costco customers typically visit the store on a bi-weekly basis, not weekly. Even looking at the time spent in the store, we see material variation: Walmart and Costco shoppers spend about 33 and 36 minutes in the stores, respectively, while traditional grocery shoppers spend about 41 minutes in the store. It’s easy to craft the narrative of a traditional grocery shopper who spends an increased amount of time obtaining all of the family’s weekly needs versus the hyper-focused mega-retailer shopper who is on a mission for a specific SKU. The court should look beyond the issues of direct access into whether or not the traditional grocery consumer will actually be harmed. But ultimately I think it’s too easy for the court to dismiss these club stores *ahem* wholesale.

The thing I got most wrong about the JetBlue/Spirit case was the judge—I believed Judge Young would get in the weeds on the facts and highlight the nuance of a shifting market. That was simply incorrect. Here, I have less faith the presiding judge (who we’ll discuss below) will take the time to appreciate the industry and read the required nuance into the pricing dynamics and what I suspect are not great documents for Kroger.

ARGUMENT: MONOPSONY UNION LABOR

![US-based Airline Mergers between 1980 and 2020 [OC] : r/dataisbeautiful US-based Airline Mergers between 1980 and 2020 [OC] : r/dataisbeautiful](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!xrZw!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9df7938f-a790-4bfb-8f14-c5fee0784ad2_4800x6000.jpeg)