In the Spirit of Competition

Richard Branson famously said “If you want to be a millionaire, start with a billion dollars and launch a new airline.” He also once said “My favorite mode of transport is hot-air ballooning,” so perhaps the airline business was not the right personal decision, but that is neither here nor there.

For airline operators, the past few years (err… decades?) have rendered the first quote painfully relevant, from Covid travel restrictions to skyrocketing fuel prices. Even before Covid threatened to shutter airlines across the globe, European airlines were starting to see the need for consolidation as many passengers turned to budget airline options to fulfill travel needs. “Low cost carriers” and “ultra low cost carriers” (LCCs and ULCCs, respectively) like Ryanair in Europe and Spirit Airlines in the U.S. have largely been the rare green shoots in an otherwise brutal market.

These ULCCs in particular go to extreme lengths to extract and protect margins. They typically only fly one type of plane, which they will most likely own, ensuring lower maintenance costs and a fungible workforce which does not have to be trained on different equipment, and further ensuring their balance sheets are less subject to vagaries of travel seasonality and cyclicality.

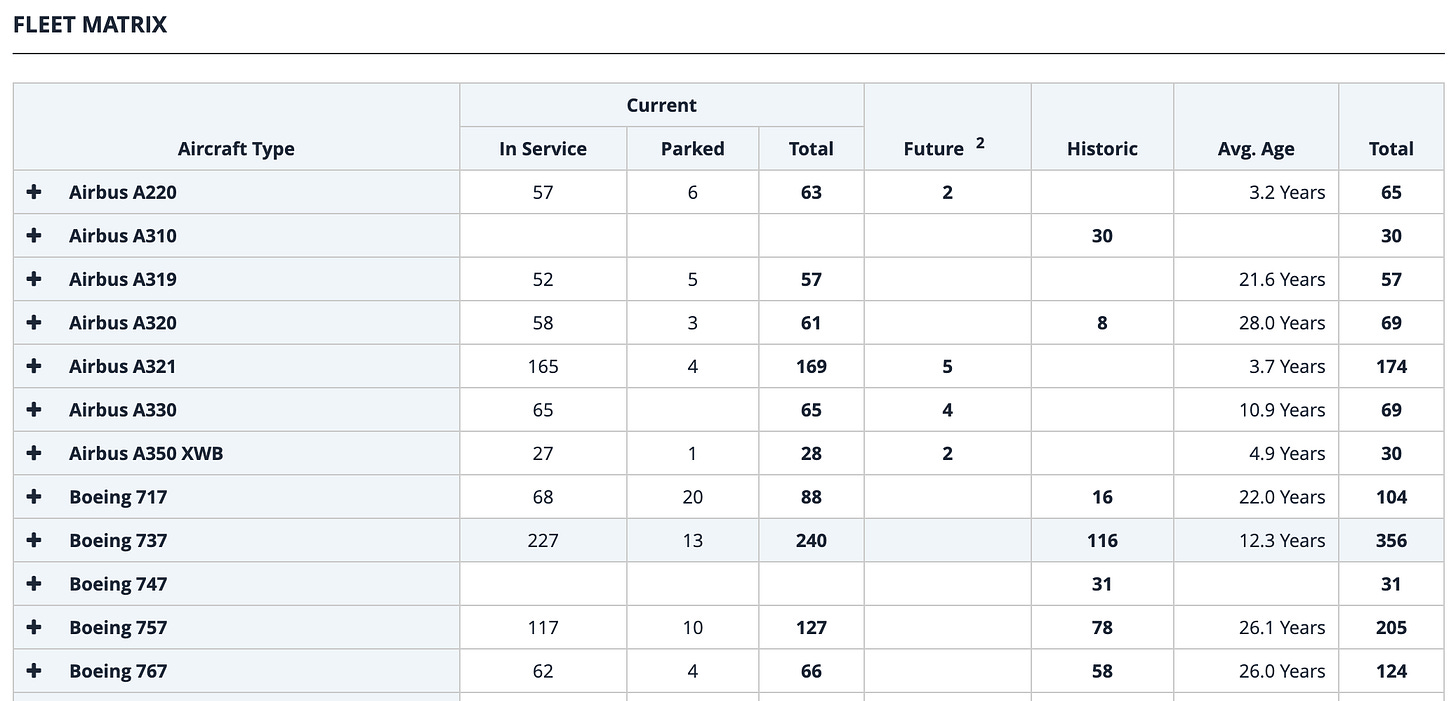

Take a look at the Delta Fleet:

And the United Fleet:

…Versus the Spirit Airlines Fleet:

Or the Ryanair Fleet:

The ULCCs also unbundle pricing to give customers the option to pay for specific seats, carry-on items, and other service upgrades (although I’ve yet to see an option that allows me to guarantee the guy next to me won’t spill his fourth whiskey coke into my lap). If you’re looking to fly into a major airport, you may be out of luck when flying a ULCC; they often opt for smaller airports (think Chicago Midway vs. Chicago O’Hare) where gates and slots (i.e. departure windows) can be obtained more cheaply. Business Breakdowns has a great podcast on Ryanair in particular, going into detail on their particularly herculean efforts to keep costs down, drive working capital negative, pay out 70-75% net income to shareholders, and somehow still grow at 15%.

So after Frontier (the U.S.’s second largest ULCC) proposed to merge with Spirit Airlines in February of 2022, it wasn’t really surprising that JetBlue made its own bid shortly after to buy Spirit Airlines, the largest ULCC in the U.S. JetBlue, which has been moving upstream from LCC (think Southwest) towards Global Network Carrier or “GNC” (think Delta, United, American) into “hybrid” status (think Alaskan and Hawaiian Airlines), sees the deal as a fast-track to creating the nation’s fifth largest carrier.

The deal itself looks pretty sweet for Spirit shareholders. After a few price bumps on the offer from JetBlue, Spirit shareholders voted to reject the Frontier bid in July of 2022 in favor of the cash JetBlue deal which offered at least $33.50/share. And while the deal also offered a $70mm reverse breakup fee and $400mm directly to shareholders in the event of a failed deal, suffice to say Spirit shareholders want to see this deal consummated. But despite the initial momentum, JetBlue’s hopes of acquiring Spirit (ticker: ) are now on life support, with Spirit trading at about half the expected closing price. (Note: the stock was <$16 just this morning when I started writing this and has now traded up over 10% into close today)

Why the (still) wide margin?

Any consolidation in a market with so few players—particularly consolidation which threatens to remove a budget option from the lineup—makes folks uneasy. In November of 2022, 25 private citizen plaintiffs filed an antitrust action in the Northern District of California under Section 7 of the Clayton Act, alleging the merger to be an antitrust violation.

Perhaps more importantly, it makes FTC Chairperson Lina Khan and Assistant AG Jonathan Kanter uneasy. The U.S. airline market has already undergone a much more severe form of consolidation than the European market. Following deregulation in the late 1970s, the U.S. market saw fewer and fewer options as time went on, resulting in the 3 major GNCs we have today: Delta, United, and American.

Chart credit: fish.substack.com

In the view of “New Brandeis” movement leaders like Khan and Kanter, big is bad. Lina Khan’s most famous work is her article from the Yale Law Journal titled “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox,” which questions whether or not a system focused on “consumer welfare” is the right one in an age of businesses which can survive on low margins, ostensibly benefiting consumers, before ultimately driving out competition and paving a pathway to more detrimental consumer pricing. It’s a fair question; however the FTC and DOJ haven’t been particularly successful in implementing these New Brandeis changes—at least not when it comes to headline wins and losses. For the most part, the case law is unchanged. Then again, you don’t turn a tanker on a dime.

Undeterred by mounting antitrust losses, the DOJ sued to block the JetBlue/Spirit transaction in March of this year in the District of Massachusetts. The complaint alleges four areas of anticompetitive threat, specifically that the merger would:

remove head-to-head competition between JetBlue and Spirit;

lead to higher ticket prices and reduced capacity;

result in less consumer choice; and

facilitate increased coordination among JetBlue and its remaining competitors.

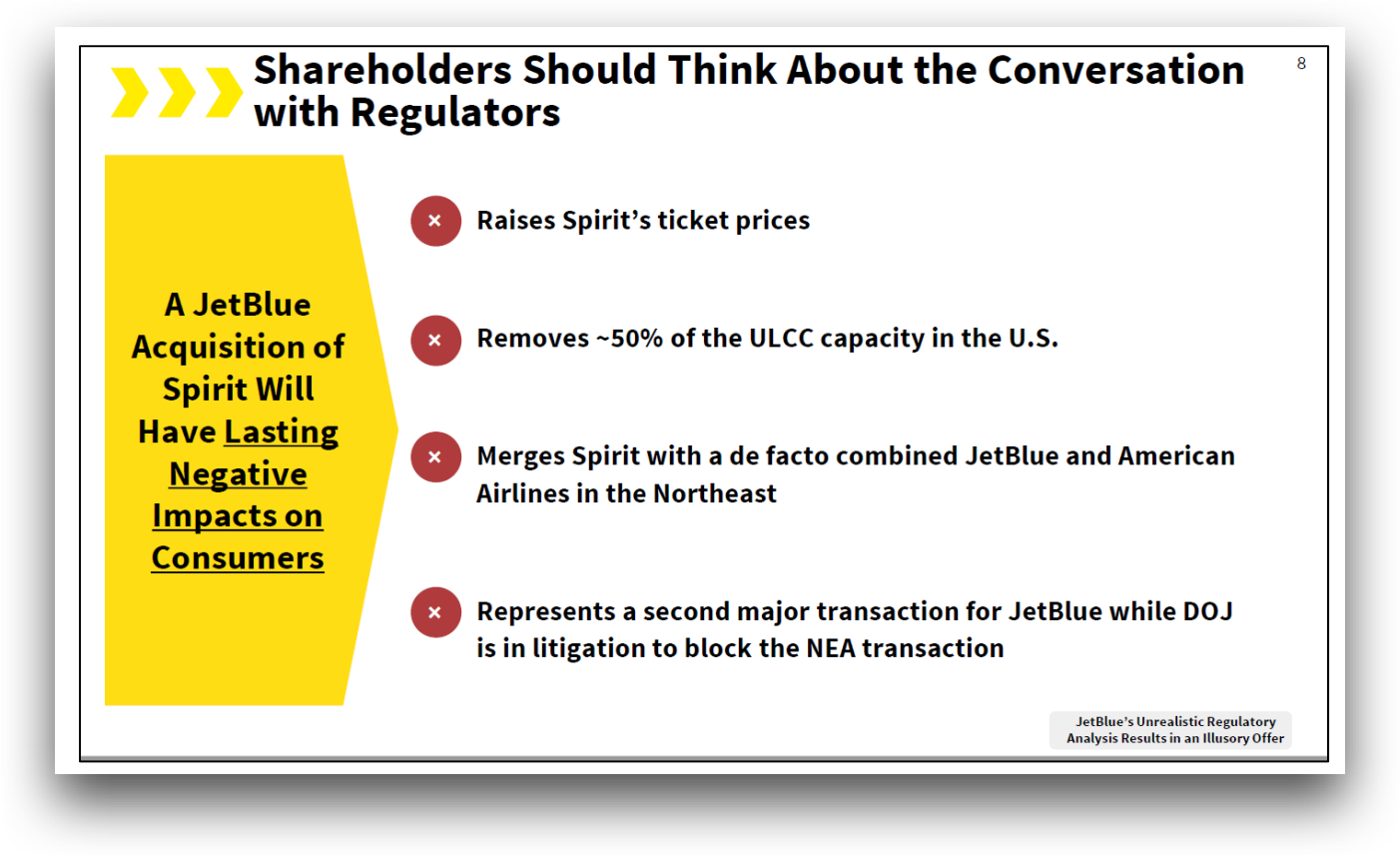

There is a slew of evidence to which the DOJ points in support of its complaint, some of it more damning than others (see, e.g., the Spirit presentation below from the pre-sweetened JetBlue deal advising shareholders that the JetBlue merger could invite unwanted antitrust attention).

But we’ll take these arguments one at a time to give context as to why I think the market odds might still be mispriced. It’s also worth a brief mention that Jonathan Kanter isn’t actually leading the charge here. He has recused himself due to the fact that he used to work at Paul Weiss, the law firm now representing JetBlue in the private antitrust action in the Northern District of California. Doha Mekki is the DOJ crusader in charge in Massachusetts, and while less is known about her own antitrust-related beliefs, it’s fair to assume she’s carrying water for the same movement to which Kanter and Khan subscribe.

HEAD-TO-HEAD COMPETITION

The Argument

The DOJ says the merger would end head-to-head competition on routes where the two airlines currently compete, as well as in any way the airlines might compete in the future, including both in expanded route offerings and overlap of business model.

What can be done about it?

Not much. If JetBlue acquires Spirit they won’t compete head-to-head anymore. But that is generally true of any merger, and therefore not worth discussing much. And the notion that this merger is bad because the airlines might compete in certain respects in the future is fairly attenuated. While the DOJ has been successful expanding the “actual potential” theory of competition at the margins, the risk is still remote.

HIGHER TICKET PRICES AND REDUCED CAPACITY

The Argument

The DOJ says that JetBlue is going to remove seats on planes and jack up prices to untenable levels. There is some evidence of this, most notably the “hot doc” that circulated due to clerical error a couple of weeks ago, confirming everyone’s worst fears: JetBlue will raise pricing by 24-40% and will remove around 24 seats per Spirit aircraft to give customers the leg room JetBlue is famous for. It worries that cost-conscious travelers will be out of luck, particularly in markets where Spirit currently dictates the prices. Spirit, the DOJ says, is the bottom-up benchmark for other airlines, sometimes referred to as the “Spirit Effect.” Any additional ULCC capacity will not come online quickly enough to meet consumer demand and stabilize prices.

What can be done about it?

There are a few things the DOJ position fails to credit.

First, the “Spirit Effect” has not always been the most talked-about effect. We used to talk about the “Southwest Effect”—the moniker for the increase in services to and from origins and destinations that Southwest recently entered. We also have the “Frontier Effect”—the name given to the effect of major airlines reducing prices to compete with the lowball fares offered by ULCC Frontier Airlines. JetBlue has had its own “Effect.” The point is, when consolidation happens, ULCCs take advantage, moving into the void left behind by the major players. The airline industry, for all its faults, is not always a stagnant cesspool. It can adapt.

These changes may not be immediate, but there’s a steady track record of ULCCs anchoring the big guys to a lower, base price. Avelo, Breeze, Sun Country, Allegiant, and Frontier all stand to benefit from the Spirit acquisition. In fact, back in June, JetBlue entered into a definitive agreement with Frontier which would see all of Spirit’s LaGuardia holdings (slots and gates) divested to ULCC Frontier. Just this morning, in a further effort to find a reasonable solution, JetBlue announced it would divest all Spirit holdings at Boston Logan airport, Newark airport, and 5 gates at Fort Lauderdale airport to ULCC Allegiant. These aren’t just random divestitures either. Newark airport is mentioned 6 times in the DOJ complaint, LaGuardia 4 times, Boston Logan 5 times and Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood twice, with Fort Lauderdale being mentioned as a key origin or destination another 13 times. If these “origin/destination pairs,” as they’re known, are the true pain points for this deal, JetBlue has surely done a good job of taking a scalpel to the DOJ’s main concerns.

Second, the document revealing the aggressive price hikes comes from a failed redaction in the private antitrust action, and is a characterization of JetBlue documents by plaintiffs’ counsel. In other words, you have to take the figures with a sizable grain of salt. We don’t know what underlying documents plaintiffs’ counsel relied upon in coming up with these figures. It could have been one of many different hypothetical, internal JetBlue projections. It could have been a recommendation from McKinsey telling JetBlue how to best merge the services. We don’t know, and we shouldn’t let a likely hyperbolized version of events dictate the thesis.

Finally, the headline numbers fail to take into account the benefits consumers will see, largely through improved service. I don’t think I’m being overly critical when I say that Spirit Airlines service is… lacking. I have flown Spirit Airlines and Frontier once in my life, respectively (both only one-way, thank god), and it’s not an experience I wish to repeat. And I’m generally pretty cheap when it comes to travel. Stick me in the cargo bay for all I care. Better that I can keep an eye on my luggage or my Taylor guitar anyway. All that is true and I still wouldn’t fly Spirit again. I’m also not the only one who thinks so. I’m pretty confident that I recall an “anything but Spirit” option on Expedia or Kayak or one of the other flight aggregators, though it looks like they have since deprecated that feature in favor of a toggle pane featuring all airlines (somebody please confirm I’m not making that up??).

I will acknowledge that for some customers price is the only relevant factor, and price anchoring exists. That is likely to always be true. And unfortunately for JetBlue, travel itself is not fungible. If Frontier or Allegiant cannot provide service to an origin/destination which the market loses through this acquisition, there is no replacement until another airline decides to buy those gates and slots. Car travel and train travel are rarely legitimate substitutes. It’s worth noting however that even Spirit’s pricing has come under fire for sneaking in hidden fees. And antitrust law is largely a body of law based on standards of reason. Antitrust law does not ask “will there be any effect on the consumer?” Rather, it asks whether or not restrictions are reasonable when weighed against the social costs of permitting such commercial activities. The history of airline consolidation says that it probably is.

LESS CONSUMER CHOICE

The Argument

The DOJ alleges that Spirit is the driving cause for other “unbundled” offerings, pointing to near-decade old comments from Delta and American executives stating that Spirit influenced low-tier pricing, and that such “innovation” is a result born of—and unique to—ULCC ingenuity.

What can be done about it?

First of all, I don’t buy it. Airlines have been looking for ways to pack planes since the dawn of time, and they’re not likely to stop any time soon. The mere fact that unbundled pricing originated with a ULCC does not mean major carriers will suddenly flip the kill switch on them once this merger closes. If a traveler won’t fly but-for the basic pricing, the major carriers will find a way to offer it to them.

But let’s assume I’m wrong, as I often am. Let’s assume that JetBlue plans to bundle everything up in one box. Let’s assume the JetBlue execs are preparing slide decks in dark, smoke-filled rooms dedicated to the sole purpose of putting all of those fees—the carry on bag fee, the checked bag fee, the seat selection fee, the pre-board fee, the landing gear fee, the bathroom use fee, the leg room fee, the having-legs fee, the qualified captain fee, and the give-a-f*** fee all back into one, nice little package.

There’s still a solution…

That solution is to require JetBlue to keep Blue Basic, JetBlue’s unbundled offering. I will grant you that this does not guarantee that all other carriers will keep unbundled offerings, but if the new JetBlue/Spirit entity offers unbundled pricing across the board (i.e., on all non-divested JetBlue and Spirit routes), then not much has really changed at all in our hypothetical post-merger world, and it seems highly unlikely Delta, United, and American would let JetBlue get away with being the only major carrier to offer such competitive pricing. We could end up with a consent order that simply says “just don’t go breaking things,” and JetBlue and Spirit go on their merry way. And Spirit shareholders would get paid.

INCREASED COORDINATION AMONG COMPETITORS

The Argument

Perhaps the most interesting element of the DOJ’s complaint—and the one the market most seems to under-appreciate—centers around its concerns of non-acquisitive anticompetitive behavior. That is to say, the DOJ is worried JetBlue will be more likely to collude with the major airlines. This is not a new concern.

Prior to any of the events we’ve discussed materializing, JetBlue had entered an agreement dubbed the “Northeast Alliance” (NEA) with American Airlines in February of 2021, whereby JetBlue and American would enjoy a combined juggernaut-like power in Boston and New York, cross-selling tickets, and sharing revenues and gate access.

The deal was questionable from the start. In New York, JetBlue and American were two of the four largest carriers. In Boston, they were two of the top three.

Under antitrust law, two things are generally true:

“Horizontal” mergers (i.e., unadulterated consumption of market share) is more suspect than “vertical” mergers, and

Partnerships or agreements not to compete are more suspect than mergers and acquisitions, because the cost of entering a partnership is so low.

While JetBlue might not technically be a direct competitor of American Airlines under the “GNC” vs. “Hybrid” delineation, they are largely the same when it comes to domestic travel. The NEA, which created an ironclad mini-monopoly in the Northeast, was exactly the type of agreement antitrust law abhors.

In September of 2021, the DOJ sued to end the NEA. Then, in May of 2023, after the DOJ filed its suit to block the Spirit acquisition, Judge Lee Sorokin in the District of Massachusetts ruled the partnership had to end.

What can be done about it?

First, JetBlue has stated it will not appeal the ruling that it must exit the NEA. It’s the correct decision if there’s any hope to be had for seeing the Spirit deal closed. But more importantly, it renders a good chunk—not all, but a chunk—of the DOJ complaint moot. The DOJ’s complaint hammers home the criticism of the deal, calling it a “de facto merger,” and highlighting the cozy benefits JetBlue obtained from American, all of which is now out the window.

Again, it’s worth contextualizing to be fair to all sides. The NEA was explicitly ruled anticompetitive and ordered to end. This is different from JetBlue independently offering to end the alliance in favor of the Spirit deal. JetBlue merely gave up the appeal. In other words, the NEA can be anticompetitive and the Spirit acquisition can be anticompetitive. It’s not an either-or situation.

But as we discussed above, JetBlue has agreed to divest the gates and routes that the DOJ is most concerned about in its complaint—namely those in New York, Boston, and Fort Lauderdale. JetBlue’s actions over the past few months have, at the very least, taken a considerable amount of wind out of the DOJ’s sails (or wind from under the wings?). It’s increasingly hard to see how this merger is any more offensive than some of the more recent airline mergers.

THE PRIVATE CLAYTON ACT CHALLENGE

What about the private action?

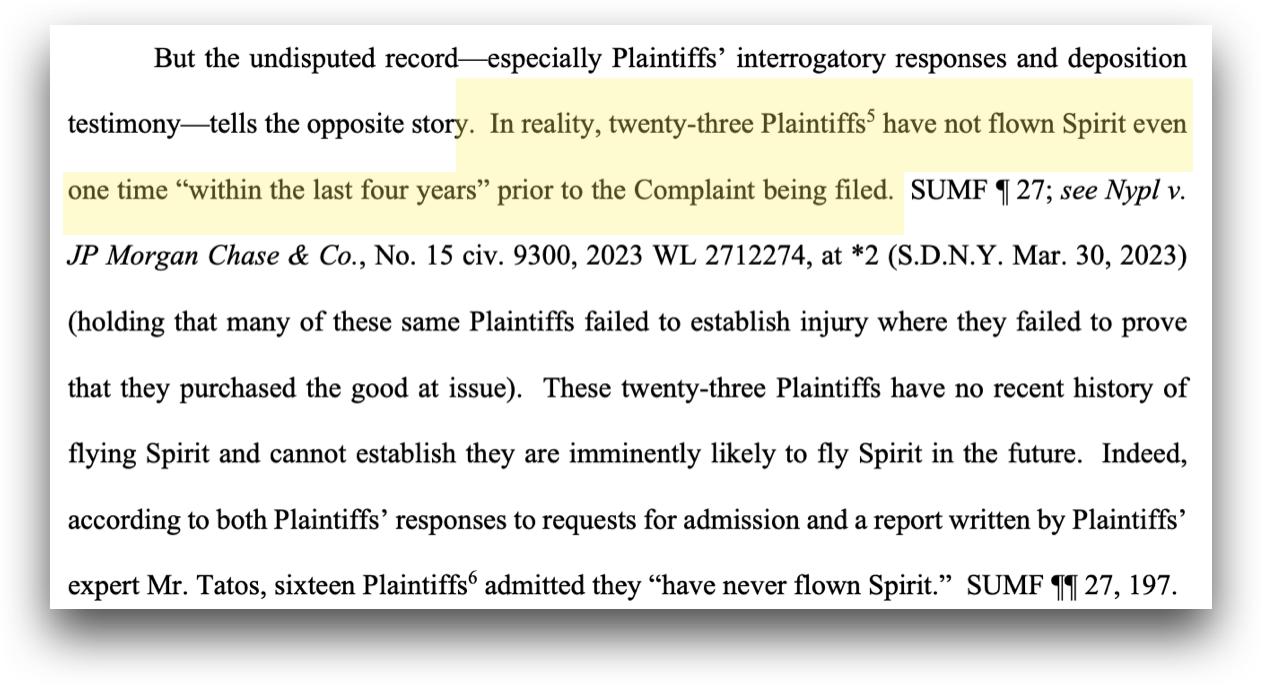

It’s hardly likely to be the deciding factor. Private antitrust actions in sensitive industries are more or less the cost of doing business. And “business” is exactly what it is for both sides. As it turns out, these plaintiffs don’t really care about Spirit airlines. Not that it really matters, but the action is a bit of a side show.

Additionally, many of the plaintiffs have sued to enjoin an airline merger before—the Delta/Northwest merger in 2008 and the Alaska Air/Virgin America merger in 2016. And despite the allegations of “irreparable harm” (you know, the type of harm where money won’t suffice to alleviate the harm done), the plaintiffs in both cases appear to have settled out of court for—you guessed it—monetary sums. Further still, plaintiffs couldn’t even remember whether or not the airlines merged, or which airlines were involved. I don’t believe “total amnesia of the facts and consequences” is generally good evidence of irreparable harm.

CONCLUSION

The main takeaway is that JetBlue has several levers it can pull—and has pulled already—to make this deal work. So far, JetBlue seems willing to do anything to save (pun intended) the marriage. The deal that the DOJ will challenge in October is not the same deal it filed suit to challenge in March.

The question that remains is whether or not the DOJ has any intent of settling, and whether or not the line they may or may not have drawn is a line that makes the deal uneconomical for JetBlue. In spite of the gaps in the DOJ’s logic, and in spite of JetBlue’s divestitures since the DOJ filed its action, this may yet be one of the DOJ’s best cases in the last several years. It’s not saying much, but it may mean the DOJ is less inclined to settle, particularly if it can obtain a ruling that expands the precedent for the New Brandeis movement.

A bench trial (no jury) is set to commence on October 16, with post-trial briefing due November 17. The judge is Judge William Young, a senior-status (semi-retired) judge who was nominated by Reagan in 1985. Libertarians beware—Judge Young will not rubber-stamp this deal simply because he’s a conservative judge. He’s earned a reputation as an even-handed arbiter over his nearly 4 decades on the bench, and neither party will pull the wool over his eyes.

It’s likely that we see a ruling early 2024.

I went long this morning following the news of the Newark, Boston, and Fort Lauderdale divestitures. It’s about 2% of my portfolio, and had it not run up so quickly I would have considered going up to 5%. This is not a “slam dunk” case, so its unlikely I ever take this up to 15-18% as I’ve done with higher conviction positions, and I will be ready to trim on news that closes the arb spread, but I do think the market has had the odds mispriced, particularly <$16. March options, which should reflect the outright likelihood of close, had it priced under 20% odds until Friday, and about 33% odds at close today. I see this as at least 50/50 odds. I am no expert in airline valuation, and the past few years make it difficult to get a read on Spirit value but-for this transaction, but I’ve heard reasonable justifications for prices ranging from $10-14. At $17.32, the equity looks to be pricing in about 20-25% chance of closing. This is one that requires an eye on any news which could influence settlement or remove roadblocks to JetBlue’s success.

![US-based Airline Mergers between 1980 and 2020 [OC] : r/dataisbeautiful US-based Airline Mergers between 1980 and 2020 [OC] : r/dataisbeautiful](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!xrZw!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9df7938f-a790-4bfb-8f14-c5fee0784ad2_4800x6000.jpeg)