The 'Lionel Hutz' Substack is now Valorem / $LQDA Update

A last look at the appellate arguments before the Fed. Cir. hearing

Lionel Hutz (Substack) is dead. Long live Lionel Hutz (Twitter). Welcome to the brand new Valorem Research page!

The past year and a half or so has been incredible as I’ve grown the Lionel Hutz blog and met some amazing investors on Substack and Twitter. I want to thank each and every one of you who has subscribed to the Lionel Hutz Substack—your support means the world to me.

As I think about the future of my legal special situations research, the logical conclusion is that a paid Substack is the only way to ensure I can continue to put out high quality—and much more frequent—research reports in 2024. Please see the “About” page on the Valorem Substack for a little more on what I hope to accomplish here, and to see if either of the paid tiers is right for you. Today’s post will be free, but future in depth articles will sit behind a pay wall.

With that… Here we go! The moment you’ve all some of you have been waiting for…. The Liquidia PTAB appeal update is finally here! This one has caused some folks on Twitter a lot of heartburn, particularly in light of the IBB 0.00%↑ and XBI 0.00%↑ struggles in the last 6 months. So we’re going to be super careful and methodical about this, starting first with a quick revisiting of the procedural posture (why we’re here), followed by a summary of UTHR’s arguments, standards of review, and finally hitting each of UTHR’s arguments in turn. Jokes and memes shall be saved for another day. This is about to get technical, as neither side has a perfect, slam dunk case. And besides, even MJ botched his fair share of dunks. I encourage everyone to view this article on Substack directly, as it will almost surely get cut off via email.

QUICK REVIEW OF THE PATENT: PTAB INVALIDITY AND DISTRICT COURT INFRINGEMENT

In case anyone is still confused, the Federal Circuit has received briefing on the validity of the ’793 patent—a patent owned by UTHR and asserted against Liquidia. Liquidia lost the district court litigation related to this patent in Delaware District Court, with Judge Andrews ruling that Liquidia would induce infringement of claims 1, 4, 6, 7, and 8 of the ’793 patent. The finding of “induced” infringement is because the claims relate to treating patients and pharma companies simply don’t treat patients, they make drugs, and we don’t expect doctors to conduct freedom to operate analyses for every patent relating to every drug they prescribe. Over the summer, we saw the District Court appeal affirmed by the Federal Circuit.

The PTAB, presented with different theories of invalidity as compared to the District of Delaware, ruled all the ’793 claims were invalid. This gives Liquidia one more shot to knock out the ’793 (again, in front of the Federal Circuit). If Liquidia wins the current appeal, it will begin commercialization of Yutrepia some time in 2024.

The ’793 patent has 8 claims, comprised of 1 independent claim and 7 dependent claims. Dependent claims are narrower versions of the independent claim, meant to survive if the independent claim falls. If I invented a method of controlling a computer with my mind, I might attempt to claim:

Independent claim 1: A method of controlling a computer

Dependent claim 2: The method of claim 1, wherein the controlling mechanism is telepathy.

We can easily see independent claim 1 is broader. It covers any method of controlling a computer. So when the guys at Xerox (yes, it was Xerox refining SRI Int’l’s work) say “Hey! We invented a way to control a computer—it’s called a mouse!” I would respond by saying “Ok, fine. My independent claim 1 might die, but I still have my dependent claim 2!” If my claim 2 survives, the patent is not dead—I can still assert claim 2 against those who infringe it.

The ’793 claims at-issue in the district court litigation are shown below. These are the claims of the ’793 Liquidia must now kill to avoid infringement and further Yutrepia launch delay.

One quick note on dependent claims—Dependent claims can also depend from other dependent claims. As you see in the ’793 patent, claim 7 depends from claim 6, which in turn depends from claim 4, which in turn depends from claim 1. Claim 8 depends only from claim 1. We’ll get to why this matters later, but suffice to say analysis around claim 7 must include all the limitations of claims 6, 4, and 1, while analysis around claim 8 must include all the limitations of claims 8 and 1.

Despite claims 2, 3, and 5 of the ’793 not being relevant to the D. Del. ruling of infringement, the PTAB found that all ’793 claims were invalid in the “mini trial” inter partes review. Specifically, it found that a personal of ordinary skill in the art would have thought all of the ’793 claims were obvious in light of 3 prior art references:

U.S. Pat. 6,521,212 (another UTHR patent);

Voswinckel JESC; and

Voswinckel JAHA.

In other words, all three of the ’212 patent, Voswinckel JESC, and Voswinckel JAHA are prior art and teach what the PTAB says they teach, otherwise UTHR wins.

Fortunately, the PTAB has already ruled that they are, and they do.

As you see in the chart below, this is the only combination that renders the ’793 claims invalid. “Ghofrani” and “Voswinckel 2006” were two other references originally ruled to be qualifying prior art by the PTAB, but later ruled non-qualifying on the PTAB’s reconsideration of its original Final Written Decision.

SUMMARY OF UTHR ARGUMENTS

UTHR sets forth 3 main arguments in support of its appeal, each with 2 subcomponents. The semi-layman-ified version of the arguments are below:

The PTAB erred by considering the “Voswinckel JESC” and “Voswinckel JAHA” abstracts as prior art

Liquidia did not include any mention of “abstract books” in its original petition for an IPR and therefore advanced this theory of distribution too late/waived its right to bring the argument up.

Even if the PTAB properly considered the “abstract book” theory, there is insufficient evidence the abstracts themselves were distributed publicly, and therefore the abstracts don’t qualify as prior art at all.

The PTAB messed up its obviousness ruling with respect to the independent claim 1

The PTAB improperly relied on hindsight to establish that the references disclosed a dose, rather than a concentration.

The PTAB did not address UTHR’s secondary considerations related to the “unexpected” nature of the results of its inhaled treprostinil claims, so the Federal Circuit should remand the case back down to the PTAB and instruct the PTAB to explicitly consider this evidence.

The PTAB messed up its obviousness ruling with respect to the dry powder claims (claims 4, 6, and 7)

The PTAB made a legal error by failing to read in the “dry powder” limitation into the claims and only considered whether “dry powder” inhalation was obvious, rather than dry powder inhalation in the specified dosage (i.e., the PTAB interpreted the claim too broadly and therefore made it a bigger target susceptible to attack).

The PTAB’s conclusion is not supported by the prior art evidence, which showed that dry powders are different from the solutions described in the prior art.

BACKGROUND ON APPLICABLE LEGAL STANDARDS

When we look at any case, it’s always important we keep legal standards in mind. You’re probably familiar with the criminal standard of proof: a person must be guilty "beyond a reasonable doubt.” In a civil case, the standard of proof is usually a “preponderance of the evidence.” That is, the plaintiff must show something was more likely than not—a much lower standard of proof than the standard in criminal cases. This makes a lot of sense to most people. We’re ok with some uncertainty when money is on the line, but we’re far less comfortable with uncertainty when a person’s freedom is on the line.

What you may be less familiar with is evidentiary and appellate standards. The illustration of standards is best served with an example:

Let’s imagine we are watching a criminal trial. The defendant is accused of some generic crime, but has asserted an affirmative defense of insanity, brought on by a clay pot that fell from a window and hit the defendant on the head. Over the course of a trial, 3 important things will happen:

The judge will make some decisions about how to run the trial (e.g., “I’m going to allow testimony from this woman who claims she saw the defendant get bonked on the head,” or “I’m going to allow this doctor to opine on whether or not a bonk on the head could cause temporary insanity.”)

You will have factual evidence and factual determinations (e.g., the woman actually testifying “this man was bonked on the head!” or the doctor saying “bonks on the head of this sort very frequently result in temporary insanity,” and the jury will say “We [believe/don’t believe] that woman was telling the truth about the bonk on the head” or “We [believe/don’t believe] that doctor was credible.”)

There will be interpretations of law (e.g., the judge will instruct the jury “In order to find the defendant guilty, you the jury must find that he had the requisite mental state; if the bonk made him insane, you cannot find he had the requisite intent to commit the crime.”)

On appeal, we talk about standards of review based largely on which of those three categories of things we need to review. For discretionary matters like whether to admit certain evidence, we generally review cases for abuse of discretion. For questions of fact, we generally review for reasonableness or clear error, depending on whether the factual determination was made by a jury or judge, respectively. And for questions of law, we generally review de novo (i.e., with fresh eyes). This also makes a lot of sense to most people. We don’t want to disrupt a jury’s (fact finder’s) interpretation of facts unless it was really wrong—after all, they hear the testimony first hand and were much closer to the evidence. But appellate judges are usually very good judges, so they will happily revisit a lower court judge’s interpretation of the law.

There are some quirks about these standards of review, and these three standards don’t actually capture the universe of appellate standards which exist across state and federal court systems (there is also an “arbitrary and capricious” standard, and technically a “no review” standard, and sometimes “clear error” becomes “clear and unmistakeable error”… you get the point).

One important quirk is that federal agencies get special rules. When a federal agency (like the PTAB) makes a factual determination, it is reviewed for “substantial evidence,” rather than clear error. It’s close to clear error—particularly when the federal agency is conducting something that kind of looks like a trial, like an IPR—but it’s not exactly the same. The “substantial evidence” standard asks:

“Was there a sufficient factual basis in the record, such that a reasonable person might have reached the conclusion of the lower court?”

The standard does not say “the finding of fact must be one a reasonable person would come to.” It allows for disagreement between hypothetical, reasonable parties.

Based on the types of conclusions UTHR is challenging, the 3 standards of review we need to be familiar with in the instant Federal Circuit appeal are:

Abuse of discretion for discretionary matters means the Federal Circuit will overturn the PTAB’s decision to admit the evidence if the decision:

is clearly unreasonable, arbitrary, or fanciful;

is based on an erroneous conclusion of law;

rests on clearly erroneous fact findings; or

involves a record that contains no evidence on which the Board could rationally base its decision

Substantial evidence review for questions of fact means the Federal Circuit will overturn the PTAB’s factual findings if they are not supported by such relevant evidence as a reasonable mind might accept as adequate to support a conclusion.

De novo review for questions of law means the Federal Circuit will overturn the PTAB’s legal conclusions if, on its own review without deference to the PTAB, the legal conclusions were wrong.

UTHR would, of course, love everything to be de novo review. They would prefer the Federal Circuit give no deference to the PTAB—who ruled against them—for any of the inquiries. Consequently, they tend to characterize the arguments as matters of law wherever possible to encourage a fresh look. Liquidia encourages the Court to think of the disputes as questions of fact to obtain a more deferential view.

With that background, let’s take a look at UTHR’s arguments.

ARGUMENT #1(A): THE PTAB SHOULD NOT HAVE ALLOWED CRITICAL “ABSTRACT BOOK” ARGUMENT REGARDING REFERENCES VOSWINCKEL JESC AND JAHA AS EVIDENCE BECAUSE THE ARGUMENT WAS NOT INCLUDED IN LQDA’S ORIGINAL PETITION

Standard of Review: Abuse of discretion

UTHR first argues to the Fed. Cir. that Liquidia’s argument that the Voswinckel references were included in “abstract books” which were distributed to conference attendees should never have been admitted to the record at all because this abstract book argument was brought forward too late.

UTHR argues that the Voswinckel JESC and JAHA “booklet” argument was not present in LQDA’s original petition, and therefore LQDA forfeit inclusion of such argument. The first part of that sentence is true. The Voswinckel references appear in the original petition, but there is no mention of “abstract books” containing all abstracts presented at the respective professional conferences. The book argument appears in Liquidia’s reply brief in support of its petition. So the process went: (1) Liquidia files petition which mentions abstracts themselves, (2) UTHR says the abstracts weren’t disclosed, (3) Liquidia replies with evidence of disclosure in abstract books.

Now, it is true that one cannot raise entirely new arguments in a reply brief—in most respects you are bound by what is contained in your original petition. But petitioners are allowed some leeway to augment their original filing. Including additional evidence to support existing arguments in response to a patent owner’s responsive arguments is generally within that freedom.

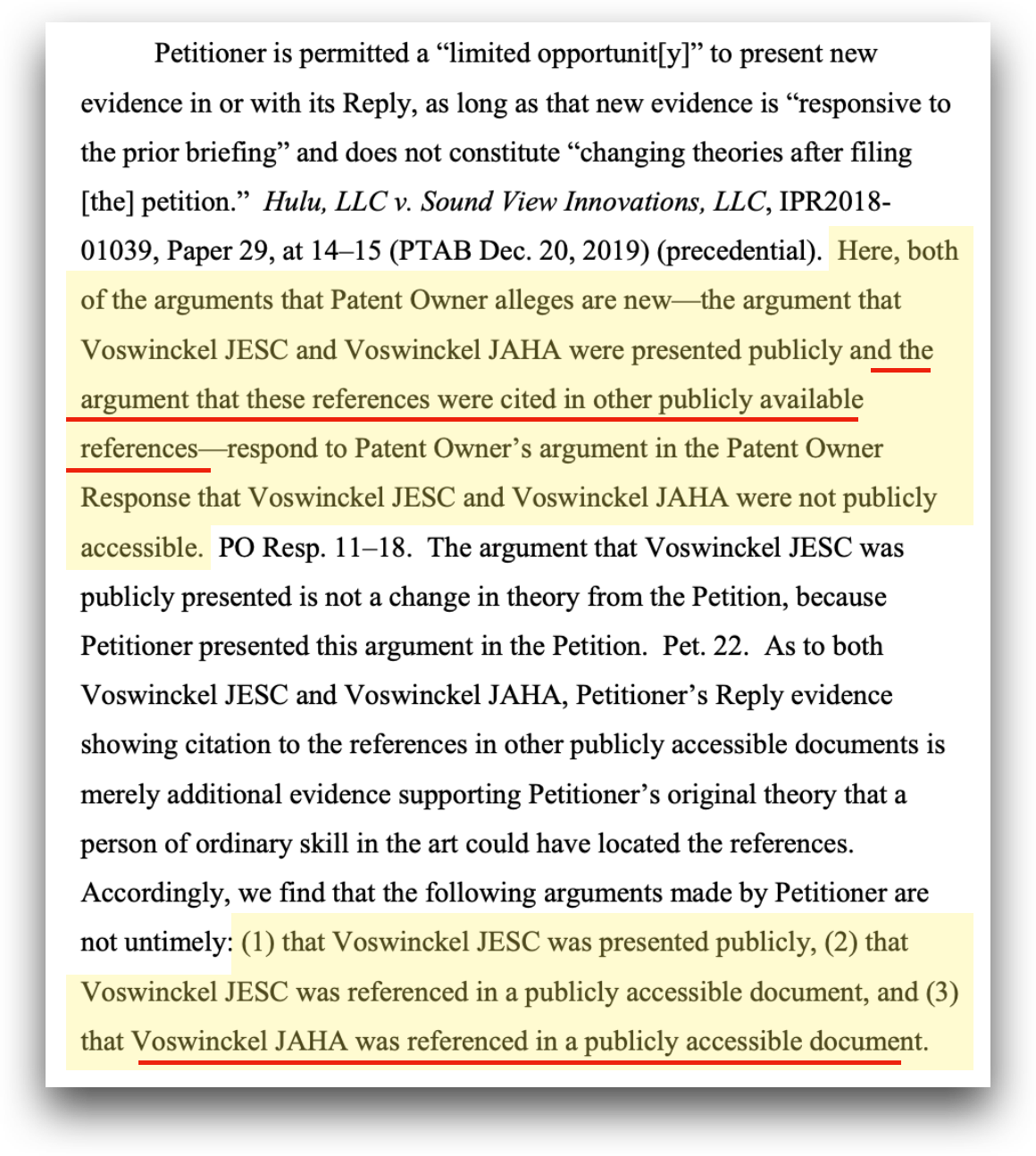

Notably, the PTAB pointed this leeway out in its Final Written Decision:

It’s important to note here that the standard of review is abuse of discretion—the decision to allow evidence or argument is within the PTAB’s discretion. So was it clearly unreasonable or arbitrary? Was it based on an erroneous conclusion of law?

Probably not. But don’t take my word for it—it helps a helluva lot more when we have a similar case to point to. And behold! We have such a case thanks to our good old friend, Twitter (R.I.P.): VidStream LLC v. Twitter, Inc., 981 F.3d 1060, 1064 (Fed. Cir. 2020). Appeals from IPR2017-00829, IPR2017-00830.

Here’s a summary of the case from law firm Winston & Strawn:

Twitter filed IPR petitions using a book by Bradford as the primary prior art reference against a patent with a 2012 priority date. The Bradford book contained both a copyright 2011 date and a “made” in 2015 date. In the patent owner’s response, VidStream argued that the Bradford book did not qualify as prior art under 102(a) because of publication in 2015. On reply, Twitter submitted additional evidence of publication in 2011, including 1) the Bradford book’s copyright registration certificate documenting publication in 2011, 2) a librarian declaration on public availability of the Bradford book in 2011 based on library MARC records, and 3) an Internet Archive website showing the book for sale in 2011. Twitter argued that the 2015 date indicates the date of reprint. The PTAB allowed the patent owner to file a sur-reply challenging the timeliness of the evidence. . .

On appeal, VidStream argued that the PTAB’s rules required Twitter to include all of its evidence in its original petition because the 2018 PTO Trial Guide states that “Petitioner may not submit new evidence or argument in reply that it could have presented earlier.” . . . Twitter responded that PTAB precedent allows a petitioner to introduce new evidence as a legitimate reply to evidence introduced by the patent owner. The Federal Circuit held that the PTAB’s allowance of new evidence did not amount to an abuse of discretion. The Federal Circuit found the Board’s actions appropriately permitted both sides to provide evidence in pursuit of the correct answer.

Sounds pretty familiar, huh?

Now, in the spirit of fairness, the “abstract book” is sort of new argument rather than purely new evidence. LQDA’s original petition did not include any reference to the books which might contain the abstracts themselves. And unfortunately Liquidia characterized JESC a bit differently from JAHA in its original petition. Liquidia stated that Voswinckel JESC was “presented at the European Society of Cardiology (JESC) Congress from August 28 to September 1, 2004 in Munich, Germany and published in the European Heart Journal on October 15, 2004.” Liquidia does not include the same “presentation” language for Voswinckel JAHA, instead simply saying JAHA was “an abstract published in the Journal of the American Heart Association on October 26, 2004.”

It was not until Liquidia’s reply brief that it asserted both JESC and JAHA were presented. So it seems possible the Federal Circuit accepts that the conference distribution evidence is acceptable in furtherance of JESC, because the original argument was that it was presented, but not for JAHA, because the original argument was only that it was included in a publicly available journal. This would of course be catastrophic to Liquidia, as we noted above Liquidia requires all of (1) the ’212 patent, (2) JESC, and (3) JAHA to qualify in order to win this appeal.

Ultimately, it’s a question of framing. UTHR seeks to cage Liquidia to the argument that the evidence must be in furtherance of the “presentation” language—language absent in the original petition for JAHA; however as the Board noted in its FWD, the only reason the presentation matters is to show that the abstract itself was made available. In other words, the presentation is not the relevant theory, abstract availability is the crux of the matter, and the additional evidence of presentation for Voswinckel JAHA is merely in furtherance of this argument. We see, upon revisiting the FWD cited above, that the Board acknowledged and credited this framing.

And on this point Liquidia has strong case law in its favor: Hulu LLC v. Sound View Innovations, LLC, No. IPR2018-01039, 2019 WL 7000067, at *6:

“For example, if the patent owner challenges a reference’s status as a printed publication, a petitioner may submit a supporting declaration with its reply to further support its argument that a reference qualifies as a printed publication.”

UTHR challenged the JESC and JAHA references as prior art, and Liquidia simply supplied additional evidence that those references qualify, albeit adding the “presentation” language in the reply for JAHA. This, combined with the standard of review, makes me believe the Federal Circuit is not going to hold that allowing LQDA evidence and expert testimony—testimony which was ultimately corroborated by UTHR’s own expert for both JESC or JAHA—represents clear error in judgment at the PTAB, particularly given the journal that Liquidia cited for JAHA is the journal associated with the conference it later referenced, and both JESC and JAHA were themselves included in the original petition. Things might be different had the JAHA journal been unrelated to the asserted conference disclosure.

Even UTHR’s case law doesn’t support its broad reading of the proposed waiver. UTHR cites Samsung Elecs. Co. v. Infobridge Pte. Ltd. in support of its claim that these “new arguments” are waived; however the case is entirely inapposite with the facts here. In Samsung Elecs. Co., Samsung overtly waived its reliance on two industry conferences—one in Torino and one in Geneva—which it later tried to use in support of its distribution theory. Samsung Elecs. Co. v. Infobridge Pte. Ltd, 929 F.3d 1363, 1370 (Fed. Cir. 2019). Just take a look at this exchange from the oral argument held at the PTAB in that case:

Q. I thought it was pretty clear from your reply brief that you had backed away [from relying on the Torino meeting]?

A. We have never taken the position before the Board or here that there was a distribution of WD4 at the Torino meeting ....

Q. But even as to the Geneva meeting .... you never relied on that alone?

A. We are not relying on the Geneva meeting ...."

The facts in Samsung Elecs. Co. are, quite simply, nothing like facts we see in this case. Overruling the PTAB on grounds of impermissible new argument is generally reserved for situations where the theory of disclosure really changes (e.g., “our original argument was that you disclosed this at a conference but now we’re saying you disclosed it when you published marketing materials a month later.”). Stating in a reply brief that the journal article referenced was also presented, in direct response to UTHR’s counterarguments of public accessibility, likely falls short of warranting waiver. And Liquidia has other evidence—namely the fact that the publication date of the journals for both JESC and JAHA predate the ’793 priority date. Still, Liquidia needs both JESC and JAHA to qualify as prior art, and the relative strength of JESC may not necessarily save JAHA. That being said, I find abuse of discretion simply too high a standard for UTHR to overcome here.

ARGUMENT #1(B): EVEN IF THE BOARD PROPERLY ALLOWED ARGUMENT OF DISTRIBUTION AT THE CONFERENCES, THERE IS INSUFFICIENT EVIDENCE TO MAINTAIN THE ASSERTION THE ABSTRACTS WERE ACTUALLY DISTRIBUTED

Standard of Review: Substantial Evidence for underlying factual findings; De novo for legal determination of “prior art” status

UTHR next argues that, even assuming Liquidia is allowed to make the argument that the abstracts were contained in abstract books and disseminated at conferences, there isn’t sufficient evidence to demonstrate the abstracts were actually distributed. UTHR points to the fact that the “abstract books” are not themselves in evidence, nor was there testimony from an actual attendee of the conference saying they recalled the abstracts being distributed in 2004. Rather, Liquidia relied on an expert witness who did not attend the relevant conferences in 2004—the European Society of Cardiology Congress and the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions Conference—to provide evidence that it was customary for presenters to distribute abstracts to all attendees, and that POSITAs would certainly have been in attendance at these conferences. UTHR’s briefing overplays this lack of evidence, but we’ll get to that in just a minute.

UTHR cites a key case in support of its contention: Norian Corp. v. Stryker Corp., 363 F.3d 1321, 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2004). This case presents a compelling quote that “testimony that it was the general practice . . . for presenters to hand out abstracts to interested attendees” is not “substantial evidence of actual availability.”

Pretty damning given we know we don’t have the actual abstract books here.

But UTHR fails to acknowledge case details and language from the district court decision (N.D. Cal.) which led to the Norian appeal, along with other evidence and other case law that supports the PTAB’s finding.

For example, the Norian case included expert testimony stating that the presentation materials asserted as prior art were only distributed to “interested [meeting] attendees,” rather than freely distributed to everyone—directly contradicting testimony that it was “customary” to distribute the materials to everyone. And this is an important distinction! Requiring attendees to affirmatively ask for abstracts is a step too far, as compared to general distributions. Indeed, the N.D. Cal. Rule 50 ruling which led to the Norian appeal suggests that “customary” evidence of free distribution may be satisfactory:

“Norian faults the witnesses for being unable specifically to recall actually having copies ready for handout. After more than a decade, however, it is understandable that truthful witnesses would ordinarily lack such powers of acute recollection. Custom and practice evidence is admissible and can, if convincing enough, prove up public accessibility. Constant v. Advanced Micro-Devices, Inc., 848 F.2d 1560, 1569 (Fed. Cir. 1988).”

This is again confirmed by dicta (i.e., non-”rule” language from the case) regarding the lack of existence of such “abstract book” materials. The Norian case history explicitly disclaims the existence of abstract books—unlike more formal records like lab notes—as "too casual" a distribution to be produced a decade after such a conference. Here, nearly two decades have passed since the respective JESC- and JAHA-related conferences.

“But the act of having copies for ready handout would ordinarily be too casual an event to generate a "ubiquitous paper trail." Consequently, corroboration was not required as long as the jury could reasonably have found, from all the evidence, that the clear-and-convincing standard was met.”

Further still, there is other case law which directly supports the PTAB’s conclusion that Liquidia’s evidence is satisfactory. While the Federal Circuit has not—to my knowledge—ruled directly on point, the District of Delaware has encountered facts which look eerily similar to the Liquidia facts, and it ruled in favor of the party similarly-situated to Liquidia.

Remember how I said UTHR overplayed its hand suggesting there was no evidence at all of dissemination? Let’s first take a look at the evidence cited in support of the PTAB’s ruling with respect to Voswinckel JESC:

…and now Voswinckel JAHA:

Compare that to the District of Delaware case SRI Int'l, Inc. v. Cisco Sys., Inc., 179 F. Supp. 3d 339, 360-61 (D. Del. 2016).

“Cisco contends that [the prior art reference] was presented at the Proceedings of the 20th National Information Systems Security Conference in October 1997. [The prior art reference] is listed in the table of contents for the conference at page 394 and Cisco has provided the paper incorporated into the conference materials with corresponding pagination. . . SRI contends that Cisco has not provided evidence that William Hunteman “attended the conference, if he presented at the conference, what he presented at the conference, or when the papers were distributed following the conference. . . The court concludes that the inclusion of Hunteman in the conference materials (independent from whether William Hunteman attended the conference) is sufficient to make it “publicly accessible."

So there you go. Delaware found that inclusion of relevant references in conference materials corresponding to days of presentation was sufficient to establish public disclosure—regardless of whether or not there was testimony from a conference attendee stating the reference was, in fact, disclosed.

In the spirit of continued fairness to UTHR, the lower court (N.D. Cal.) decision and its language is not binding upon the Federal Circuit here, nor is the District of Delaware case. But remember, when it comes to the factual determinations (like whether or not the abstracts were distributed) the relevant standard is substantial evidence, which only asks whether a reasonable person might arrive at the same conclusion. The District of Delaware, looking at nearly identical facts, did come to the same conclusion. And while the Federal Circuit doesn’t have to listen to Delaware’s instructive guidance, it’s worth noting that Delaware is a very popular patent venue. Delaware received almost 20% of all patent cases in 2022. The Delaware judge who issued the SRI Int’l opinion was Judge Sue Robinson, who famously drafted new patent case rules and presided over one of the busiest patent dockets in the country. The point is, Judge Robinson is a pretty reasonable adjudicator of this type of case, and the Federal Circuit would do well to follow the same logic.

ARGUMENT #2(A): LQDA’S CLAIMS THAT VOSWINCKEL JESC RENDERED THE ’793 OBVIOUS IGNORES THE FACT THAT THE PATENT DISCLOSES ABSOLUTE AMOUNTS OF TREPROSTINIL, NOT MERELY CONCENTRATIONS

Standard of Review: Substantial Evidence

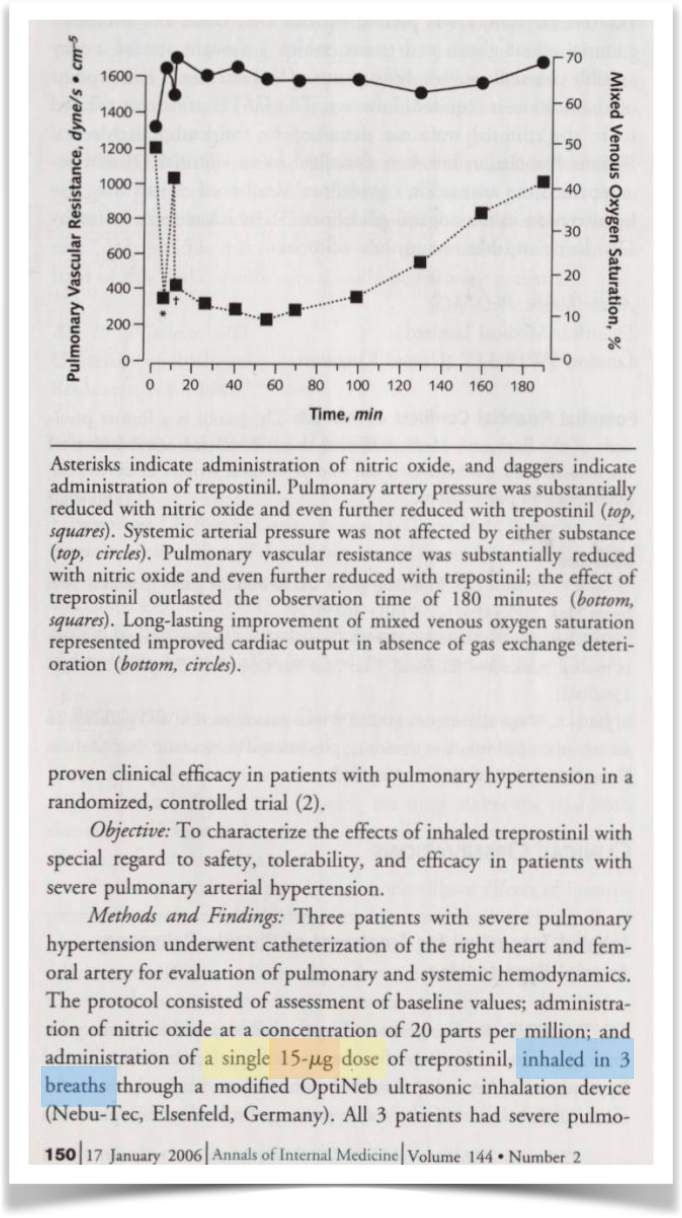

UTHR’s next argument is that LQDA cites to JESC in support of the claim that the dosage levels specified in the ’793 patent—15 micrograms to 90 micrograms of treprostinil—were in the prior art. As we see in the above excerpt of the patent claims, we know that the prior art must render the range of 15-90 μg of treprostinil obvious, yet no evidence supplied by Liquidia enumerates these quantities.

This is somewhat true.

The JESC reference—which the PTAB relied upon in part to determine the dosage was obvious—does only mention concentrations of drug solution placed into the nebulizer, specifically: 16, 32, 48, and 64 μg/ml. However, the PTAB’s conclusion did not rest on JESC alone. The PTAB also credited both parties’ experts Dr. Hill and Dr. Gonda, who opined on conventional nebulizer volumes, from which the PTAB derived its ultimate opinion on dosage quantities:

Additionally, UTHR’s own expert confirmed that nebulizers were, in his experience, always at least 1 milliliter, and usually 3-5 milliliters, confirming the lower bound of Liquidia’s expert testimony and corroborating the standard range:

Consequently, it is reasonable for the PTAB to arrive at the conclusion that dosages within the patented range were disclosed in the prior art. Each of the four ranges suggested by JESC has some midpoint within the disclosed 15-90 μg patented range. And though it may be reasonable to suggest that the 32, 48, and 64 μg/ml don’t necessarily disclose 15-90, as each has points within the 1-5 ml range which lay outside the 15-90 μg patented range (i.e., a POSITA may not immediately recognize 15-90 μg as obvious if there was some other confounding factor which suggested that at lower concentrations a higher volume must be used, meaning a disclosure of a 32 μg/ml concentration does not necessarily correspond to every point within the 1-5 ml volume range), the entirety of the 16 μg/ml concentration, when multiplied by the 1-5 ml volume range (for a total of 16-80 μg of dosage), falls within the patented range. In other words, the disclosure of a 16 μg/ml concentration, combined with the expert testimony, must disclose a dosage which precludes the validity of the full 15-90 μg dosage range.

Again, to UTHR’s credit, they raise a valid, if not fairly inconsequential point. UTHR points out that inhalers cannot be 100% efficient, and patient breathing patterns may not guarantee that all dosage volume leaving the inhaler is delivered to the patient, meaning that the disclosed concentrations, when combined with the expert testimony fill volumes, may yield lower dosage volumes. But Dr. Hill—Liquidia’s expert—did opine on the “nebulized” volume (i.e., the amount of aerosolized liquid), saying that at least 1 ml of liquid would be aerosolized, and Dr. Gonda—another Liquidia expert—confirmed the “delivery.”

While there may be inefficiencies in delivery, UTHR clearly mischaracterizes the Board’s conclusions and support. UTHR states that the PTAB’s decision is unsupported by any evidence:

But that simply isn’t true. Dr. Gonda pointed to at least three different nebulizer labels, each of which had a fill volume of greater than 1 ml, and then opined that, based on his own professional medical experience, the amount actually delivered would be 1-5 ml depending on the inhaler.

Moreover, the ’793 patent itself betrays UTHR’s logic, at least to the extent it applies to losses attributed to patient inhalation (e.g., losses due to particles sticking to your throat versus losses attributed to nebulization within the inhaler). The patent claims delivered dosages in the range of 15 to 90 μg. In the patent specification, the support points to a delivered aerosol volume (the volume coming out of the inhaler) of 15 μl. Combined with the 1000 μg/ml concentration of treprostinil, the support reaches the conclusion that a lossless 30 μg was delivered in 2 puffs of the inhaler.

In any event, the Board did consider these arguments, and found Liquidia’s expert testimony to be reliable:

The risk to Liquidia here is that the Federal Circuit finds Dr. Gonda’s and Dr. Hill’s testimony insufficient to bridge the gap between fill volumes and dosages (after all, they’re doctors, not medical device engineers); however it isn’t entirely unreasonable to credit their knowledge of delivery, given the expected medical results they would anticipate based on such delivery, and the fact that doctors should be knowledgeable about the efficacy of drug+device combos. If you need 100mg of an active ingredient to treat symptoms and anything less than 100mg won’t suffice, you’d hope your doctor would know that all 100mg might not be delivered with a particular device. And again, given the substantial evidence standard, it seems more than fair to credit the PTAB’s findings as as at least one possible reasonable conclusion.

ARGUMENT #2(B): THE PTAB FAILED TO CREDIT UTHR’S SECONDARY CONSIDERATIONS AS TO WHY THE INHALATION OF TREPROSTINIL RENDERED “UNEXPECTED” RESULTS, MAKING THEM PATENTABLE AND NONOBVIOUS OVER THE PRIOR ART

Standard of Review: Substantial Evidence for underlying questions of fact (e.g., whether obviousness is supported by factual determinations the PTAB did credit); De novo with respect to any legal error for failing to credit secondary considerations

UTHR spends a considerably shorter amount of time arguing that the Federal Circuit should remand the case back to the PTAB so that the PTAB may consider these “secondary considerations”—particularly that dosing a patient in 1-3 breaths created an “unexpected result”—it allegedly failed to consider when arriving at its Final Written Decision.

I’ll similarly spend little time on this argument for obvious reasons. This characterization is almost entirely in bad faith. Failure to credit, sure. Failure to consider, no.

The UTHR argument cherry picks a quote from the original Final Written Decision (the one that allowed Voswinckel 2006 and Ghofrani as prior art references), which is based on the fact UTHR’s inclusion of “unexpected” results evidence in its sur-reply. Ignoring for a moment the fact that raising such arguments in a sur-reply effectively waives the arguments, a key issue for UTHR remains. These “unexpected” results the PTAB allegedly failed to credit were based on a comparison of treprostinil to iloprost which, though it is another vasodilator, has significantly slower transpulmonary transit time, making the comparison inadequate, particularly in light of the prior art on which the PTAB did rely.

In the Revised PTAB Decision, the PTAB addresses the argument head-on and cites the relevant prior art:

Why didn’t the Board cite to UTHR’s evidence of unexpected results? Well, for starters, when it comes to the alleged unexpected results over treprostinil, there isn’t any. UTHR, in its POR (Patent Owner Response), provided no evidence other than the conclusory statement that high doses of treprostinil were known to produce limited side effects. It immediately follows that conclusory statement with a citation to a comparison of treprostinil with iloprost.

It’s worth noting that it is not necessary for the PTAB to expressly say “Liquidia’s evidence is better.” The decision is supported by cited, sufficient evidence. UTHR cites one case in support of the alleged error of law (rather than fact) regarding the failure to credit its argument: In re Van Os, 844 F.3d 1359, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The case makes the following conclusion:

“[t]he agency tribunal must make findings of relevant facts, and present its reasoning in sufficient detail that the court may conduct meaningful review of the agency action.”

The PTAB must make a relevant finding of fact in enough detail to make the Federal Circuit review meaningful. The Federal Circuit has the PTAB’s decision, and the prior art on which it is based. It is not necessary to credit the weaker argument. If the Federal Circuit is unsatisfied with the PTAB’s justification, it may overturn the PTAB’s conclusions. UTHR’s case does not preclude the PTAB’s reasoning and conclusion thereon.

It’s one of UTHR’s weakest arguments, which is why they spend so little time on it. However it allows UTHR to make a key demand—remanding the case back to the PTAB. It’s a low chance of success, and UTHR would lose again at the PTAB due to the dissimilarities between treprostinil and iloprost, but the delay alone would be a victory for UTHR.

ARGUMENT #3(A): The PTAB failed to consider all claim limitations when evaluating the obviousness of the dependent claims and failed to account for evidence that precludes the Voswinckel references from being used to show dry powder dosing.

Standard of Review: De novo

UTHR asserts the PTAB did not actually consider all of the relevant facets of the dependent claims, and therefore the conclusion it drew with respect to obviousness was flawed. We talked at the top about dependent claims, and noted that dependent claims are more narrow than independent claims. If an independent claim fails, the more narrow dependent claims survive (or rather, might survive), because they include all of the “claim limitations” of the independent claim, plus additional limitations. Dependent claims can be dependent from other dependent claims, but the important bit to remember is that a dependent claim is fully subsumed within the independent or dependent claim from which it depends.

In order invalidate the ’793, the prior art must disclose all the claim limitations (e.g., to invalidate “Dependent claim 2” in the sample diagram the prior art would have to disclose the claim elements for Independent claim 1 and Dependent claim 2). Further still, if the claim elements come from multiple sources, the prior art would have to include motivations to combine them. In other words, all claim limitations to an invention could theoretically be out in the public, but if no one has suggested they be grouped together in the claimed way, or a POSITA can’t provide testimony that the grouping would have been obvious, the patent may yet survive.

The exact claim element UTHR says the Fed. Cir. did not consider is the “dry powder” elements of the dependent claims. Taking a look at the ’793’s dependent claim 7, we get the below claim when you read all limitations from the independent claims (and higher up dependent claims), as shown by the bracketed (i.e., substituted) language:

It’s worth noting here that the PTAB’s decision isn’t as thorough as you might hope on this front. They did variously talk about the dry powder limitations supplied by the ’212 patent prior art (which we’ll talk about more below), but what the PTAB didn’t do is discuss the motivation to combine a specifically dry powder treprostinil with the dosing elements supplied by the Voswinckel references.

Rather, they merely noted that the ’212 patent supplied the dry powder elements and then stated that a POSITA would have been motivated to combine the 3 references needed, without further discussion tying this motivation to combine back to the full claim elements in each asserted claim. It’s a bit sloppy, but likely not fatal. UTHR’s argument that the dry powder elements were not addressed at all clearly exaggerates the failings of the PTAB’s decision.

ARGUMENT #3(B): Even if the PTAB’s analysis was procedurally correct, there was insufficient evidence to support a finding of obviousness for the dependent claims

Standard of Review: Substantial Evidence

UTHR’s final argument is that, regardless of process, the conclusion that the ’793 dependent claims are obvious is simply not supported by the evidence.

So how do we arrive at the conclusion that the ’793 limitations were disclosed and motivation to combine existed, such that the substantial evidence burden is met?

Let’s first look back at the limitations themselves. Dependent claim 7, described above in 3A, is the “most” dependent claim (it depends from dependent claim 6, which in turn depends from dependent claim 4, which in turn depends from independent claim 1). If you “read in” all of the claim limitations to dependent claim 7 you end up with the below claim:

The various colors you see are the “elements” of the claim, or the things that have to be present in the prior art with motivation to combine in order to invalidate this dependent claim.

Now, let’s look at where the support for Liquidia’s invalidation assertion comes from: the ’212 patent and the Voswinckel references.

The ’212 patent describes—and claims—the use of a dry powder treprostinil formulation (“UT-15”) to treat primary and secondary pulmonary hypertension. The patent discloses both the use of inhaled treprostinil and the pharmaceutically equivalent salt/powder of the relevant size.

What is missing from the ’212 reference is the dosing (1-3 “single event” breaths of 15-90μg). We get these from the Voswinckel references.

Here is the Voswinckel reference (the second screenshot is present in both JESC and JAHA):

So we see that all the claim elements are at least arguably present, and that’s important considering we’re on appeal with a substantial evidence standard of review. But what about the motivation to combine? That comes from Liquidia’s expert, Dr. Hill.

Now, there are plenty of jokes people make about using expert testimony to supply the needed motivation. Patent holders get annoyed that patent challengers often find the claim elements in the prior art then get some questionably-qualified scientist to show up and go “yep, I would have been motivated to combine those things!” It’s a fair critique of the system. The case law underpinning the permission of this type of testimony is KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398 (2007), and it has been the subject of considerable criticism. But at the end of the day, expert testimony is usable, provided the motivation to combine is not merely “conclusory.” For example, if a challenger was trying to invalidate a patent for a television with a handle on it, the challenger’s expert would need to say something along the lines of, “the invention of a television with a handle on it is obvious because we have prior art of televisions and prior art of handles, and a POSITA would be familiar with both and would have known at the time consumers wanted electronics to be portable”). If that italicized justification is present, the expert testimony is usable. And here, Liquidia did exactly that.

Here’s the PTAB quoting Liquidia’s expert, Dr. Hill’s, testimony regarding the motivation to combine. The sentence in the middle provides the justification:

UTHR hopes the Fed. Cir. takes a similar approach to a 2016 decision, In re NuVasive, Inc., in which the Fed. Cir. vacated and remanded the PTAB’s decision, asking the PTAB to rule on exactly why the POSITA would have been motivated to combine the references. The Nuvasive PTAB allowed expert testimony which had quite literally no reason underpinning the motivation, and such conclusory testimony isn’t good enough, even in light of the KSR decision.

In the present instance, it would not be sufficient to say “we knew about dosing dry powder treprostinil in this way, so it would have been obvious.” The rationale must be present. But as we can see, there is a clear justification present for the assertion that a POSITA would combine the ’212 patent with the Voswinckel references: patient compliance.

The most interesting aspect of UTHR’s argument though is not whether the evidence is sufficient, but rather if Liquidia shot themselves in the foot in the District Court case by arguing that the ’793 patent was not enabled. UTHR makes a secondary argument here that, because Liquidia argued at the District Court that the claims of the ’793 were not enabled (i.e., reading the claim does not tell you how you’d actually practice the patent), Liquidia cannot now argue that combining the prior art would lead a POSITA to expect the benefits of the claimed ’793 treprostinil inhalation by combining the prior art as suggested. It largely boils down to “if you said you didn’t know how to make this invention in the District Court litigation, how can you now say it’s obvious to combine other prior art references to yield the invention?”

On its face, it sounds somewhat reasonable. If I say “I don’t know how to make this invention” after reading your patent, it seems weird then that I could point to things that preceded your invention and say “but also if you combine these things you’ll get the invention you claim!” How can I know the prior art combo will result in the invention if I just said I don’t understand how to practice the invention?

The simple truth is that these arguments are quite different, and Liquidia’s enablement arguments at the District Court should not preclude them from arguing the ’793 results are not unexpected now. But don’t just take my word for it—let’s show our work.

One way a patentee may show that the invention is novel over the prior art is to show that the patented invention has unexpected results. This is especially true for chemical compound patents because we often see patents covering not just the compound itself, but also the manner in which the compound is used (e.g., using inhaled treprostinil to treat PAH). That compound may have been originally invented to treat one specific disease, but it may be a genuinely novel invention to use that same compound—alone or in conjunction with other treatments—to treat an entirely separate disease.

In these scenarios, the patent examiner should look to whether or not the results derived in the new treatment are actually unexpected when compared to the use of the compound in treating the old disease. By way of a short example, if the creators of Finasteride (used to treat an enlarged prostate) knew that patients developed a full head of hair throughout the Finasteride clinical trials and documented such results, we would not allow a newcomer to claim a patent on “using Finasteride to treat hair loss,” because those results were fully expected, albeit unintended.

But what about enablement? How can it be that a patent is not enabled (i.e., the method of practicing the invention is unknown) but the results of the patented invention are known or expected?

We can address the difference between enablement and unexpected results with a very simple example. Let’s pretend we’ve got a little magnesium cube sitting in front of us that is 1cm x 1cm x 1cm. It’s already been milled to cubic perfection. We have to use this cube and we do not get to 3D print another. Other than the perfection of its measurements, this magnesium cube is unremarkable in every way—it’s a solid and entirely pure cube.

Now let’s assume I tell you we want to make the cube float when placed in water, and we aren’t allowed to add anything to this cube. In fact, the requirements of this exercise state that we have to keep the outside of the cube perfect.

The way to make the cube float is to make it less dense than the water. So using your critical thinking skills you come up with an idea to hollow out the cube. You know that magnesium has a density of 1.738 g/cm³, and water has a density of 1 g/cm³, so assuming we’ve got a 1cm³ cube in front of us, we need to remove about 3/4g without changing the volume the cube will displace.

“Easy!” you say. We’ll just cut out a sphere in the center of this cube! The largest sphere that can fit inside a cube has a volume about 47% smaller than the volume of the cube itself, so if we get pretty close to that (i.e., remove about .8 g), we should be more than covered!

If we are successful in hollowing out the cube, the cube will have a property that will not be novel at all: it would float in water. This would be an entirely expected result. We know this already from that simple math, above.

But what I could not tell you is how the hell you would actually go about making this cube. To my knowledge, there is no device in existence that can excavate a solid object without making any holes or blemishes of any kind whatsoever.

That is the difference between unexpected results and enablement.

UTHR says that Liquidia betrayed its own arguments in this appeal—the argument that the ’793 did not contain “unexpected results” necessary to warrant patent protection—because it argued at the District Court level that the ’793 patent was not enabled. Liquidia’s expert, Dr. Gonda, cited many “gaps” in the prior art that would prevent a POSITA from actually being able to practice the ’793 invention, including, for example, the fact that nebulized inhalers are not compatible with dry powder compounds. Dr. Gonda’s District Court testimony was that, in his expert opinion, the ’793 did not tell you how to make the damn thing.

But that is not the inquiry here. The current argument on appeal is whether or not the prior art, after disclosing the claim limitations and providing motivations to combine them in the way the ’793 claims, would yield unexpected treatment results. The treatment results—regardless of ability to practice the invention—are expected, and the PTAB ruled so. UTHR’s attempt to conflate enablement with expectation of results is therefore likely to be fruitless.

I am still long LQDA 0.00%↑ and have not made any changes to the position recently. The Federal Circuit hearing will be broadcast live via the Federal Circuit’s website, and I will be in attendance on Monday. Each side gets 15 minutes to present oral argument, and the Court will likely rule any time between 2 days after the hearing and 2 months after the hearing. If Liquidia wins, I expect the stock to trade in the $12-15 range, and I expect commercialization of Yutrepia will occur mid-2024. Liquidia will continue to face patent litigation hurdles from UTHR, but the newly-issued ’327 UTHR patent will not result in a regulatory stay as was the case with the ’793, and Liquidia likely has strong arguments to invalidate the patent.

Wait the Substack is dead but the Twitter is alive? Or the Substack is now Valorem but the Twitter (or X 🙄) is still Lionel Hutz?

Tremendous amount of work on this, Lionel! I love our chances with LQDA here. Thanks again for all you’ve done and shared with us. If you had to guess, would you think the ruling was going to be closer to 2 days or 2 months?