Waiting with Bated Breath for Liquidia Corp.

It’s been a minute! I’d love to tell you all that I’ve been grinding away, bettering myself over the past few weeks, but the simple truth is that I’ve been indulging in the Twitter victory. Part of that indulgence has been eating a steak dinner or two. Another, much larger part of that has been eating popcorn during Twitter’s collapse into a hot pile of garbage.

We watched obvious—yet somehow still elegantly efficient—phishing scams play out in front of our eyes, after Elon announced anyone could buy their way into the magical realm of blue check mark “verified” account status. Before we talk Liquidia, let’s take a look at some highlights which popped up before Musk put a pause on the new verification system:

Ahh yes. A flawless rollout.

Is this “bad for brands”? Seems probable. Is this a “free-for-all-hellscape”? Looking that way. Is this “Plunging us into a shared delusional state as the very fabric of reality hangs on by a thread tied to the phallus of the world’s least stable human”? Now we’re talking. Whatever it is, it has been damn fun to watch. In fairness to Elon, there’s a new verification system getting implemented next week. We’ll see how that goes. And though I could quite literally pull screenshots of these parody accounts all day, all good things must come to an end.

To all who followed along with Twitter arb play—welcome back, and thank you for bearing with me during my hiatus. To the new subscribers—welcome.

I’m not sure any litigation will ever be quite so entertaining as the Twitter v. Musk matter. I’m not sure I’ll ever feel anything ever again. But I aim to make these bearably educational, at the very least, as I transition from covering the most ridiculous arb play in memory to more rote arb matters. It’s also important that, to the extent possible, I get these things right. As a result, my posts may continue to be erratically spaced as new opportunities arise intermittently and as I investigate them between other commitments.

Anyway. . .

If you’re a true legal nerd, maybe you’ve been holding your breath for another litigation arb article. Maybe you’d love to hold your breath, but you actually suffer from pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), which makes that sort of thing quite hard. Maybe you use an inhaler for your PAH. This is not a forced segue at all.

If you do use an inhaler for your PAH, it probably says “Tyvaso®” on the side. That’s because, for folks with PAH or pulmonary hypertension with interstitial lung disease (PH-ILD)—both potentially fatal diseases—Tyvaso is the only inhaled treprostinil game in town.

TREPROSTINIL AND PULMONARY HYPERTENSION BACKGROUND

Pulmonary hypertension sucks. It really sucks.

Pulmonary hypertension, which is a group of diseases that causes high blood pressure in the arteries of the lungs, comes in 5 different forms (“Groups 1-5”). A lot is unknown about what causes each version of the disease, and without a cure, doctors are left treating symptoms which progressively get worse over time and regularly lead to death.

Treprostinil is important. Really important.

Tyvaso (active ingredient: treprostinil) is what’s known as a prostaglandin drug, and it’s manufactured by United Therapeutics. Tyvaso is approved for and used in treatment of patients with PAH (WHO “Group 1”) and more recently PH-ILD (WHO “Group 3”). In the United States, there are reportedly 5,000-10,000 patients in Group 1 and 30,000 patients in Group 3, though in speaking to pulmonologists, I’ve learned the number of Group 3 patients is likely to be double that.

Tyvaso isn’t the only prostaglandin drug available for PAH and PH-ILD patients—in fact, even United Therapeutics has other prostaglandin drugs available as injections (Remodulin) and oral tablets (Orenitram)—but Tyvaso, which comes in nebulizer and dry powder forms, is the only inhaler. Other prostaglandin drugs made by other manufacturers, as with Remodulin and Orenitram, are either administered orally or delivered via IV infusion. Neither of those options is very pleasant.

Oral treprostinil has limitations on the amount of active ingredient that can be delivered, and is therefore typically prescribed first in a patient’s treatment cycle before becoming unsuitable for more aggressive, late-stage disease. It also has horrific GI side effects. Still, it’s better than the IV treatments, which require a subcutaneous pump that often leads to sepsis and considerable injection site pain. Sadly, for patients with pulmonary hypertension due to lung disease, everyone eventually ends up on IV treatments as the PH-related diseases progress.

Inhaled treprostinil sits between oral and IV delivery as the last line of defense before patients move to the IV treatments. And while certain side effects are generally better than the other options—no oral administration means no GI effects, and no IV means no sepsis and injection issues—patient compliance has been mediocre at best. Historically, United Therapeutics’ inhaled treprostinil was only available in a nebulizer inhaler, which required 3-4 daily sessions, nightly preparation of a saline mixture, charging of a nebulizer device, and routine nebulizer cleaning. Perhaps more enjoyable than sepsis, but not great. So when, in 2018, United Therapeutics announced it was pursuing a dry powder version of inhaled treprostinil which would require a smaller apparatus and less burden on the patient, it was a welcomed revolution in PAH treatment. The fact that the DPI version required as many as a dozen breaths for a dose, up to 4 times daily, was an annoying aspect of an otherwise great improvement.

United Therapeutics also had the patents to back up its new DPI inhaler. These patents related both to the manufacture of the treprostinil dry powder and the method of treatment. Consequently, United Therapeutics has had a legal monopoly on the bridge between oral and injected treprostinil.

And United Therapeutics will do just about anything to protect this monopoly.

THE PULMONARY HYPERTENSION MARKET

With only a few thousand new cases of PAH and PH-ILD per year, you might be thinking, “Why does United Therapeutics care so much about what happens with these patents?”

Well, it turns out you don’t need a lot of patients taking your drug to make a lot of money. You just need to extract as much money as possible from the patients who are taking your drug.

How much money are we talking?

This is where you might interject with “Surely you can’t put a number on the value of human life!” And I’d generally agree with you. But it turns out sometimes you can put a value on human life. For United Therapeutics, each PAH or PH-ILD patient covered by Medicare and taking Tyvaso was worth approximately (err, exactly) $107,489 per year in 2015. By 2019, United Therapeutics had raised the price of the most common Tyvaso prescription to $358,632 per year, making Tyvaso the 14th most expensive drug in the U.S. that year.

It’s no surprise then that this golden goose is juicing United Therapeutics’ top line. All in all, last year United Therapeutics did $483mm in total revenues from Tyvaso sales, with revenues mostly coming from PAH prescriptions alone (Tyvaso was only approved and launched for PH-ILD in April of last year). In the nine months ending September 30, Tyvaso sales moved up to over $630mm ($601mm of that was gross profit). Just recently, United Therapeutics announced that Tyvaso revenues hit a $1 billion annual run rate.

The numbers are falling in line with projections made by BTIG Research and Strategy’s Robert Hazlett in February of this year:

“We estimate more than $1 billion in peak use of Tyvaso DPI in PAH and a potential $2 billion (plus) opportunity for PH-ILD, given the lack of competition and unmet need.”

That last clause is doing a lot of heavy lifting. Right now there is no competition for the Tyvaso inhaler. But that could be changing.

LIQUIDIA & THE DISTRICT COURT LAWSUIT

In January of 2020, after years of development, Liquidia Corp. (ticker: ) filed a New Drug Application (“NDA”) with the FDA for Yutrepia, a generic form of the inhaled treprostinil. The stock began a rapid ascent in anticipation of commercialization. But shortly thereafter, in June of 2020, United Therapeutics filed suit against Liquidia for patent infringement of two Tyvaso manufacturing-related patents:

U.S. Patent No. 9,604,901, entitled “Process to Prepare Treprostinil, the Active Ingredient in Remodulin®” (the “’901 Patent”), and

U.S. Patent No. 9,593,066, entitled “Process to Prepare Treprostinil, the Active Ingredient in Remodulin®” (the “’066 Patent”).

The suit triggered an immediate regulatory stay, preventing Liquidia from commercializing Yutrepia.

One month after filing the complaint, in July of 2020, United Therapeutics filed an amended complaint in the Hatch-Waxman litigation asserting infringement of an additional Tyvaso delivery-related patent which had issued the month before—U.S. Patent No. 10,716,793 (the “’793 Patent”), entitled “Treprostinil Administration by Inhalation.”

Not surprisingly, Liquidia ($LQDA), which has negligible revenues from a promotion agreement with Sandoz for injectable treprostinil, took an immediate hit, reversing all of its post-NDA-filing gains and then some:

These three patents all have about 5 years left on their lifespan: the ’066 and ’901 patents both expire Dec. 15, 2028, and the ’793 patent expires May 14, 2027. So when it comes to commercialization of Yutrepia, is Liquidia out of luck until 2029?

Nope.

It turns out Liquidia certainly will not have to wait until 2029. It might have to wait until the ’793 expires in 2027, and probably (my opinion) won’t have to wait beyond 2024. But this case is a procedural nightmare, so strap in!

THE USPTO INTER PARTES REVIEWS

When a party gets sued for patent infringement in federal district court, it’s pretty common these days for the Defendant to run to the USPTO Patent Trial and Appeals Board (“PTAB”) and say “Hey bozos! This patent your examiners granted—the one which I’m supposedly now infringing—should have never been issued!”

Of course, they say it a little more nicely, but that’s the gist. The Defendant from the district court litigation becomes a “petitioner,” asking the USPTO to reconsider the patent issuance in a proceeding called an inter partes review (“IPR”). These reviews are entirely separate from the district court litigation, and they’re limited to challenging the patents for failure to satisfy 35 U.S.C. §102 (“102 grounds” otherwise known as “novelty”) or 35 U.S.C. §103 (“103 grounds” otherwise known as “non-obviousness”).

And that’s exactly what Liquidia did.

With the district court litigation still pending, Liquidia asked the PTAB to institute an IPR for all three of the United Therapeutics patents asserted against it. The PTAB granted IPRs for the ’901 and ’793 patents but declined to institute an IPR for the ’066 patent.

The declined IPR on the ’066 patent wouldn’t matter in the end. Eventually Judge Andrews at the Delaware District Court would rule the ’066 patent to be invalid, knocking the ’066 out of the federal court litigation.

In December of 2021, Liquidia got a victory at the PTAB: 7 of the 9 claims of the ’901 patent were ruled invalid in the ’901 IPR. Rather than risk a binding ruling that the entire patent (already weakened by an unfavorable claim construction for Untied Therapeutics) was invalid, United Therapeutics agreed to drop it completely from the district court litigation. The agreement to drop the ’901 is contingent upon the construction being upheld on appeal, but is almost certain to hold.

And just like that—there was just one patent left in the district court litigation.

In July of this year, Liquidia got more good news: the PTAB invalidated the ’793 patent claims. It looked like Liquidia was in the clear. Combined with the other wins, it appeared that United Therapeutics was out of patents and out of hope for halting Yutrepia.

THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE PTAB AND THE DISTRICT COURT

Unfortunately for Liquidia, Judge Andrews at the district court did not agree with the PTAB’s decision, and refused to stay the district court litigation.

How can this happen?

Well, we could probably talk for hours about administrative law, “Chevron deference,” and differences in claim construction standards between the USPTO and federal district courts, but suffice to say the standards for evaluating invalidity are—perhaps unsatisfactorily and almost certainly problematically—different between the PTAB and district courts, and this has led to many issues. In short, it’s usually easier to invalidate an issued patent at the USPTO than it is in federal district court (colloquially, the PTAB judges are referred to as the “Patent Death Squad,” which is literally the only hardcore-sounding title you can ever receive as a lawyer). Some people dispute the effects of these differences, but hey—numbers don’t lie.

Still, district court judges will often stay litigation while the IPR is pending, waiting to see if the litigation before them becomes moot. This is largely due to the fact that PTAB decisions and district court patent decisions both get appealed to the same place (the Federal Circuit) and PTAB decisions usually get there faster. If the PTAB ruling gets appealed and the Federal Circuit invalidates the patent(s) being asserted in the district court litigation, any work the district court judge has done on the case is all for naught. Also, litigation costs quite a bit of money, and judges understand that fighting a battle on two fronts is usually an unfair procedural burden on a party with fewer resources, particularly when one front of the litigation might become superfluous.

Given that background, you might assume that, being a reasonable guy and all, Judge Andrews might stay the district court decision while the IPR was pending.

But he didn’t. Instead, Judge Andrews pressed on, denying the stay due to the fact that Liquidia filed its motion after trial had already concluded. He then issued his ruling that said, among other things: “Liquidia didn’t provide the ’793 is invalid,” and “Liquidia will induce infringement of the ’793 patent,” and “PTAB, you’re not the boss of me.”

This led to conflicting opinions.

On one hand, the PTAB said the ’793 claims were invalid. On the other, Judge Andrews at the district court said Liquidia had failed to show any of the ’793 claims were invalid, and that Liquidia would induce infringement (i.e., Liquidia would make consumers infringe, since the actual act of infringement is the delivery method).

How do we resolve these differences between the PTAB and the district court?

The PTAB’s invalidity ruling only becomes binding on the District of Delaware after it has been appealed to the Federal Circuit. In other words, there is some level of parity between the PTAB and district court rulings right now. Should the Federal Circuit uphold the PTAB’s invalidity decision, Judge Andrews’ district court ruling is effectively reversed, and Liquidia wins.

For those still paying attention, that means Liquidia has two paths to victory:

the Federal Circuit upholds the PTAB decision to invalidate the ’793 patent, OR

the Federal Circuit reverses the district court’s infringement rulings

Option (1) is the preferred—and faster—option. If Liquidia is successful in its appeal, Liquidia expects to start Yutrepia commercialization in mid-2024. If Liquidia is unsuccessful, the appeal stemming from the district court will take longer, and is less likely to succeed.

LIQUIDIA’S PTAB APPEAL TO THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT

So will the Liquidia PTAB appeal succeed? I think so.

The Federal Circuit upholds PTAB decisions wholesale in about 3 out of every 4 appeals. The remaining quarter of cases are split between complete reversals (~10%), mixed results (~8%) and dismissals (~8%). For the alleged infringer, a dismissal (usually on jurisdictional grounds) of a PTAB decision of invalidation is a win.

So statistically, Liquidia has a >80% chance of complete victory on the PTAB appeal.

The appeals out of district court litigation don’t bode quite as well when the appellant has been ruled to infringe (i.e., when the Federal Circuit needs to overrule the district court, as is the case with Option 2, above). But the numbers are not a write-off. And remember, Liquidia only needs one of these two hands to hit. According to a Gibson Dunn report from 2019-2020, the Federal Circuit reversed district courts on non-obviousness invalidity issues about 35% of the time, and reversed district courts on infringement issues about 16% of the time.

When taken in sum, the probability of at least one of those things occurring—for my math nerds out there: (P(A ∪ B ∪ C))—is over 90%.

I think the odds are even better than that.

That’s because the PTAB victory hinged upon two key abstracts being considered as 102(b) prior art—the “Voswinckel JESC” abstract and the “Voswinckel JAHA” abstract. Robert Vozwinckel, the author of Vozwinckel JESC and Voswinckel JAHA also happens to be an inventor on the ’793 patent. In other words, he may have precluded himself from obtaining a valid patent by way of his own disclosures of the inventive material.

THE INVALIDATING PRIOR ART

If the patent examiners missed these references when deciding to issue the patent, why should the Voswinckel abstracts be invalidating prior art now?

To fully understand this, we have to understand what counts as invalidating “prior art.” To make matters more complicated, we have to understand what counted as invalidating prior art back in 2006 (our patentability framework was amended via the “America Invents Act” in 2013, so all patents filed before March of 2013 need to be analyzed under the old regime).

Under the pre-AIA 102(b), a reference is considered prior art if:

the invention was patented or described in a printed publication in this or a foreign country or in public use or on sale in this country, more than one year prior to the date of application for patent in the United States. (emphasis added)

Of course, nothing in the law is ever simple. What counts as a “printed publication”? Do abstracts like Voswinckel JESC and Voswinckel JAHA count?

It’s not a perfectly clear call, but I think so.

To qualify, the references have to have been sufficiently disclosed to the public. By way of example, reading an abstract aloud at a conference or merely printing one single copy and then burying that copy deep in an obscure library usually won’t cut it.

The good news here is that the abstracts were very clearly printed in 2004—before the critical May 2005 permissible disclosure date, as you can see from the below photocopies of the abstracts.

Voswinckel JAHA:

Voswinckel JESC:

As far as accessibility goes, each of these abstracts was found in a multiple real, reputable libraries:

Further, we even have a declaration from a librarian at the British library saying that both Voswinckel JAHA and Voswinckel JESC were available at the British Library in 2004.

British Library Declaration (Voswinckel JAHA):

British Library Declaration (Voswinckel JESC):

On top of all that, Liquidia has backup arguments:

Backup argument #1 is that these abstracts were each presented at a conference

JESC abstract was presented at the 2004 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Congress

JAHA abstract was presented at the 2004 Scientific Sessions of the American Heart Association Conference

Backup argument #2 is that other articles known to professionals in the field cited to these Voswinckel abstracts, meaning it was clear that these abstracts were not hidden away, inaccessible to the public

I’m going to briefly dispel Backup Argument #2 first. The articles to which Liquidia cites were actually from June and July of 2005 (just too late for the critical May 2005 date). Why is that a problem? Well, Liquidia is trying to say “See?? The Voswinckel abstracts were available as of their publication date, because other people in the industry cited to them later!” While they’re probably right, these later citations don’t actually prove that the Voswinckel abstracts were available in 2004. They prove they were available in June and July of 2005.

As for determining the credibility of Backup Argument #1, courts have dealt with similar situations before. In a 2004 Federal Circuit decision In re Klopfenstein, the Court said an entirely oral presentation without slides or printed materials was certainly not a qualifying 102(b) prior art reference. The Court laid out a framework of the following factors to help guide assessing whether a disclosure at a conference is a 102(b) prior art disclosure:

the length of time the display was exhibited,

the expertise of the target audience,

the existence (or lack thereof) of reasonable expectations that the material displayed would not be copied, and

the simplicity or ease with which the material displayed could have been copied.

It’s hard to tell at this point how successful the Backup Argument #1 will be. While we don’t know how long the abstracts were displayed, nor do we actually know it was printed and distributed, we do know a couple of things. We know the audience expertise was high—these were niche medical conferences, after all. We also know that, in 2004, people weren’t quite as digitally connected as they are now, so it was pretty common for conferences to print out the materials and circulate them among attendees. All in all, this is a totality-of-the-circumstances kind of test, and it seems like a coin flip.

But remember, these are backup arguments.

THE PTAB RECONSIDERATION

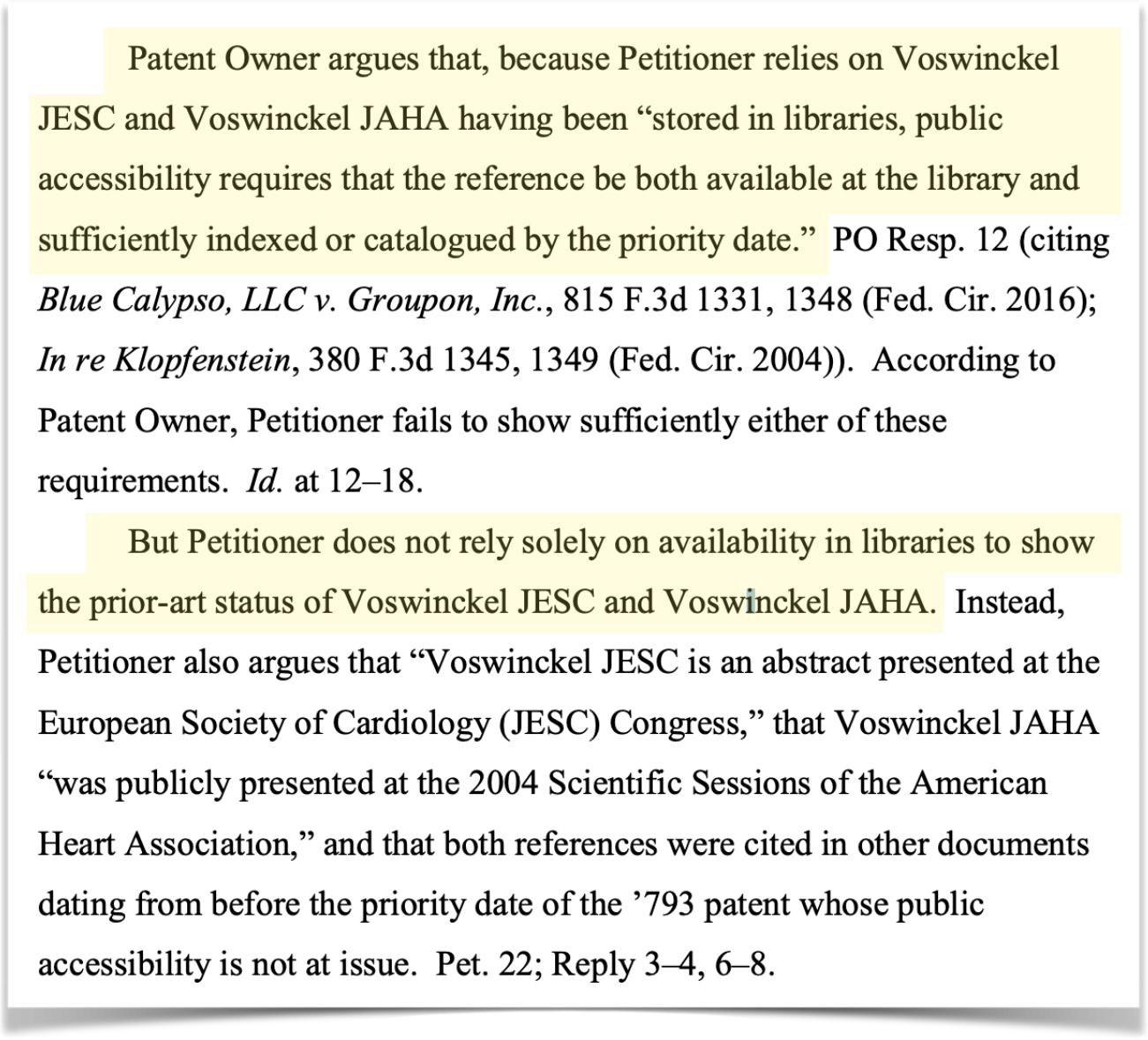

Even assuming the backup arguments fail, the primary Voswinckel availability argument seems like a slam dunk. If I’m the Federal Circuit, what I’m getting from the PTAB is a pretty clear case of (1) the inventor disclosing his exact invention more than 1 year before applying for the patent and (2) those references containing the disclosure being available in multiple accessible libraries.

Or at least that’s what the Federal Circuit should be getting.

This is where it’s important to know that the PTAB judges—called Administrative Law Judges (“ALJs”) aren’t real judges. At least, not in the traditional sense. ALJs are practitioners, law professors, etc. who decide that a government job isn’t a terrible retirement plan. Some ALJs are great. Some not so much. All of them make mistakes.

There’s a safety valve at the PTAB to help deal with these mistakes and the trickier cases. This safety valve—called the Precedential Opinion Panel (“POP”)—acts like a mini-appeal and prevents the Federal Circuit from a deluge of PTAB-specific issues.

When the PTAB’s Final Written Decision came out, United Therapeutics noticed something.

The ALJs didn’t show their work.

What the ALJs should have said was “Liquidia’s primary argument around availability is satisfactory. We hold that Liquidia is correct, and that these other backup arguments are pretty cool, too.”

What they actually said was this:

Maybe nothing jumps out at you. But what jumps out at me is that the ALJs never said “Yes, the primary argument is good.” They just went straight to “there are other arguments.”

The POP noticed this too, and though they declined to rule on this themselves, they did direct the ALJ panel to reconsider their opinion, specifically:

As if this case needed any more complexity, the current procedural posture is now as follows:

This mandate for the PTAB to spend additional time reconsidering its ruling just to add in those magic words “the primary argument is sufficient” seems like an unnecessary formality that won’t result in a United Therapeutics victory. So why then, if this whole POP/PTAB reconsideration thing is just catching the PTAB on a technicality, is United Therapeutics pressing it?

Delay. Delay. Delay.

Every day that Liquidia doesn’t have Yutrepia on the market is several million dollars in revenue that United Therapeutics is able to generate. The delay is the victory.

APPELLATE TIMELINE ON THE PTAB RULING

Let’s assume the PTAB Board upholds the PTAB Final Written Decision and the Federal Circuit appeal presses on. When will we find out about the results of the PTAB appeal?

The Federal Circuit typically takes 42 days from argument to decision to rule on PTAB patent decisions, but we aren’t at the argument stage yet. United Therapeutics asked the Federal Circuit for additional time to file its principal and response briefs over Liquidia’s objection, and the request was granted. United Therapeutics now has until December 14 to file. Meanwhile, every day that Liquidia doesn’t have a ruling is another day of commercialization lost. I expect argument to be in February or March, and a final decision in late April or early May.

NEAR TERM LQDA/YUTREPIA OUTLOOK POST-APPEAL

Where does share price go if they win on the PTAB appeal?

Probably back to where it was trading before the lawsuit, in the $10 range. That’s a double from the current ~$5 price.

Why that range? Because Yutrepia hadn’t yet received FDA approval when the suit was filed in 2020. Sure, in June of 2020 Liquidia was aiming for FDA approval by the “PDUFA date” of November 2020, (Yutrepia wouldn’t actually receive its tentative approval until November of 2021) which meant it was looking at a 5-6 month runway to commercialization, rather than the 1.5 years until the likely mid-2024 commercialization now. But the approval status in june of 2020 was an unknown. Now, Liquidia has the Yutrepia approval, removing the overhang of uncertainty. Further, the United Therapeutics litigation—including the automatic 30-month regulatory stay—was a known risk when the stock was trading at $10 in June 2020, per the 2020 May 10-Q. There are other considerations convoluting the comparison of Liquidia now to Liquidia then, including the fact that Liquidia underwent a merger in the same time period to acquire the de minimis Sandoz/Remodulin promotional rights. All in all however, a double seems like a reasonable place to start for a near-term move on a Federal Circuit win.

But what about physician adoption of Yutrepia? Does Liquidia stand to gain 50% share or more of the of current Tyvaso patients? And if they do, will that mean 50% or more of the combined $3 billion+ market for PAH and PH-ILD. What about the clinical trials United Therapeutics is pursuing to use Tyvaso to treat idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)? Will Liquidia be able to sell into that market as well?

Answering those questions requires a few major assumptions.

PAH AND PH-ILD COMMERCIALIZATION GROWTH

Let’s start with the drug pricing and market share. In the U.S., generics are dispensed 97% of the time, when available, yet generics only account for 18% of drug expenditures. There’s good reason for that discrepancy. Even after generic drugs hit the market, name brand pricing tends to stay elevated for some time, often increasing by 50% or more in the months leading up to—and following—a generic release. Because of these hikes from already-high starting points, and because generic manufacturers don’t need to invest in the clinical trial pipeline the way name brand drug companies do, generics tend to be priced 80-85% lower than their name-brand equivalents. In other words, Liquidia should have no problem quickly gaining 50% market share if pricing its inhaled treprostinil at 15% of the going rate.

But I don’t think Liquidia will have to price Yutrepia so low to gain substantial market share.

For starters, the massive drop in pricing usually occurs when there are numerous generic manufacturers which continue to dilute the market. However, there are presently no other companies seeking approval for generic DPI treprostinil (we’ll get into why exactly that is later). When you have only one generic in the market, pricing stays high. Let’s take a look at Blue Cross/Blue Shield pricing data for the adoption of Lipitor generics:

When there’s only one generic, prices stay relatively tight (in this case with the generic priced about 75% of the name-brand). So expecting Yutrepia to be priced below 60-70% of Tyvaso is likely a mistake. And at 60-70% of the current Tyvaso price, Liquidia will be generating around $250,000 per patient per year.

On top of that, Yutrepia isn’t so much a generic as it is, well… better. It’s more effective and more patient-friendly. Yutrepia is manufactured using Liquidia’s proprietary “PRINT” technology, which has allowed Liquidia to produce inhaled particles of uniform size that better penetrate the lungs, thus requiring fewer breaths and inhaler cartridges than Tyvaso. It’s also stable at room temperature, increasing portability and decreasing storage burden on patients—a huge improvement over Tyvaso. Less friction on patients means greater patient compliance, and doctors know this. Between eagerness of patient/doctor adoption and decreased costs to insurers (even if modest), Yutrepia is likely to gain substantial market share quickly without having to undercut Tyvaso’s price.

So how long will it take for Liquidia to gain real market share?

Looking at the same Blue Cross/Blue Shield data for generics adoption in the U.S., we see that in cases of 7 or more generics hitting the market at the same, time, generic adoption happens fast, with >50% adoption in the first year being typical:

Individual generic adoption happens more slowly, as is seen in the first year of the sole-Lipitor generic being made available (2011):

It might be tempting then to handicap Yutrepia adoption at ~10% market penetration/year, but in my opinion, Yutrepia is likely to see more rapid adoption (something closer to ~50% in two to three years) largely due to those improvements over Tyvaso we discussed. Moreover, while the United Therapeutics litigation has prevented commercialization, Liquidia has not stopped prepping for the Yutrepia rollout, now led by Chief Medical Officer Dr. Rajeev Saggar, a pulmonologist with deep industry ties.

So if all goes to expectation, 50% of the Tyvaso market share at 60-70% of revenue gets us to around $300mm/year starting around mid-2026 or 2027. Assuming Robert Hazlett’s projections are correct, and that the existing market for United Therapeutics’ Tyvaso exceeds $3 billion, Liquidia’s inhaled treprostinil revenues could feasibly approach $1 billion/year as a base case in the not-so-distant future as PH-ILD adoption continues to grow.

Not bad for a company with a $310mm market cap.

LABEL EXPANSION & LONG TERM YUTREPIA GROWTH

Now let’s also assume that Tyvaso ultimately gets approved for IPF. The inhaled treprostinil unlocks another opportunity for both United Therapeutics and Liquidia.

Why—if clinical trials are mostly unsuccessful—am I so sure we can make the assumption that United Therapeutics will obtain FDA approval for IPF? Well, for starters, if you’re pursuing approval for a respiratory drug and you make it to Phase III trials, as United Therapeutics has done, you’ve got about a 64% chance of getting to market. Decent odds compared to drug development in general, but a far cry from a slam dunk.

However, these are indication expansion clinical trials (clinical trials for a medication which is already approved for the treatment of other diseases) which typically have higher likelihood of success. We don’t know what the outcome will be with certainty—it’s still early in Phase III, which means United Therapeutics is recruiting patients, and recruiting for Phase III clinical trials takes a lot longer than Phase I or Phase II due to the number of patients that need to be involved. We won’t actually know about the the IPF-indication results until June 2025.

More important to my estimation of the study’s success though is an overview of how inhaled treprostinil actually works. Patients who have idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have scarred or dead lung tissue which is no longer capable of absorbing oxygen. Oral and injected treprostinil are problematic for these patients because of something called V/Q mismatch, which occurs when part of your lung receives oxygen without blood flow or blood flow without oxygen. Treprostinil, as a vasodilator, expands the arteries to allow for more blood flow. But oral and injected treprostinil act on the whole lung, causing the arteries to open up in both the good tissue and the bad tissue. Inhaled treprostinil is different, and only opens up arteries in the good portion of the lung which actually comes into contact with the treprostinil. As a result, it seems highly likely that patients with IPF will see substantial benefits to inhaled treprostinil.

Now you might think, “But United Therapeutics is the one getting the approval, not Liquidia!” And you’d be right. However, under the 505(b)(2) pathway (the drug + device combo), if and when Tyvaso is approved, Liquidia can add the IPF indication to its label, so doctors will be prescribing Yutrepia for IPF shortly after United Therapeutics gains Tyvaso approval for IPF (around Q3 or Q4 2025).

OTHER GENERIC MANUFACTURERS AND CONTINUED PRICING POWER

You might also be thinking: “Won’t we have to worry about more generic(s) taking United Therapeutics and Liquidia market share and diluting pricing like those charts above show? There won’t be two manufacturers forever!”

In theory, future entrants have the fewest hurdles—United Therapeutics spent the money on development of the drug and Liquidia is spending the money to litigate the patent claims. A third (and fourth and fifth and sixth . . .) entrant would be free from both of those investments, and could result in prices crashing down for everyone.

However, drug manufacturing and approval is not a quick process. Contract manufacturers (“CMOs”) schedule manufacturing years ahead of time (Liquidia, for example, has entered into a multi-year agreement with LGM Pharma, who is in turn the U.S. intermediary between Liquidia and Korean manufacturer Yonsung Fine Chemicals). If another entrant wants in on the inhaled treprostinil game, they probably aren’t coming to market any time soon since none have even filed for approval. And with the uncertainty around patent validity, other possible competitors are likely to sit this one out until clarity emerges.

Still, if the money is compelling, why aren’t we seeing other companies taking a swing and filing for approval?

Probably a combination of two things: (1) additional patent coverage by both United Therapeutics and Liquidia and (2) trade secret knowledge surrounding the manufacturing of inhaled treprostinil.

Allow me to explain a little further:

Liquidia has one patent related to inhaled treprostinil delivery (U.S. Pat. No. 10,898,494 entitled “Dry powder treprostinil for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension”). United Therapeutics, despite the losses in the instant litigation, maintain a portfolio of non-asserted treprostinil patents directed both to manufacturing and delivery (e.g., U.S. Pat. No. 9,701,611 "Treprostinil salts"). If you want to go to market with a dry powder inhaled treprostinil, you have to do so with a drug + device combo. This drug + device combo has to avoid infringing the remaining valid United Therapeutics patents as well as the Liquidia patent. These patent claims are broad enough that inventing around would require a somewhat heroic effort.

Perhaps even more important than the patent portfolios is the intellectual property that United Therapeutics and Liquidia have not patented (i.e., like the formula for Coca-Cola, kept as a trade secret). Liquidia began pre-clinical work on the inhaled treprostinil formula back in 2015 but didn’t actually complete its phase 3 study and get around to filing an NDA until March 2020. All in all, it took 6+ years to get to the tentative 505(b)(2) approval. And even that seems quick. Until Liquidia had its inhaled treprostinil, no one other than Mannkind (in partnership with United Therapeutics) had discovered a way to make the extremely hygroscopic treprostinil a shelf-stable dry powder. Without the right excipient, formulation, and storage method, treprostinil will pull water out of the air and become unusable. Even Mannkind’s compound—the Tyvaso DPI—needs to be refrigerated and is not stable for long at room temperature. So while other potential PAH focused companies might see the PAH and PH-ILD market as a gold mine opportunity, the R&D required for a stable treprostinil is extensive and no overnight affair. A new entrant cannot simply go to Wuxi and demand 1,000,000 doses tomorrow.

So how long do Liquidia and United Therapeutics have to take advantage of a duopoly market? Probably a while. It’s almost certainly at least 5 years, and more likely closer to 10. And each year that Liquidia and United Therapeutics don’t have additional competitors, they will be charging patients north of $250,000 for inhaled treprostinil treatment.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS & LONG-TERM UPSIDE

Is there anything else to be excited about with Liquidia?

Maybe. Liquidia continues to work on its “PRINT” technology (referenced above), which is a probably-cGMP compliant manufacturing process used for particle engineering. “cGMP” basically means “fit for commercial purposes,” so while it may be used for large-scale manufacturing of Yutrepia and other drugs in the near future, its present use is more suited to drug-candidate manufacturing. Nonetheless, Liquidia is working with GlaxoSmithKline to expand the applications of PRINT and may result in licensing revenues down the road. It’s hard to know what impact PRINT might have on the bottom line in the future, but Liquidia expects negative cash flows until Yutrepia can be commercialized, so it’s not a near-term savior on its own.

As for current cash and burn rates, Liquidia sold 11,274,510 shares on April 12, 2022. Between that offering and $9.4mm excess proceeds from re-financing long-term debt, Liquidia generated almost $65mm from financing activities in the nine months ending September 30, 2022. The company now has almost $100mm of cash on hand to help stave off another offering before Yutrepia’s commercialization phase.

I am long . We should have clarity on the PTAB ruling in the next month, though I expect the PTAB to confirm their prior ruling and provide additional explanation on the sufficiency of the Voswinckel references. The Federal Circuit argument would likely be late in Q1 and and opinion would follow in mid- to late-Q2. At that point, I expect the share price to double from current levels. While it's too early to speculate on share price following United Therapeutics label expansion clinical trials, the additional IPF indication would increase treatable patients and lead to substantial additional upside. Downside should Liquidia have the PTAB ruling overturned (by the PTAB itself or by the Fed. Cir,) is likely around $3-4 for the stock (i.e., 2019 lows, pre-NDA filing).